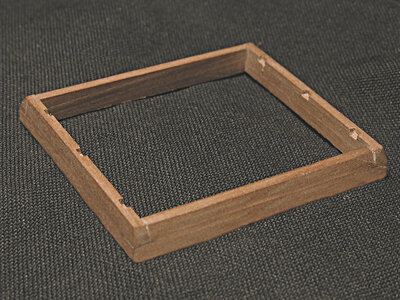

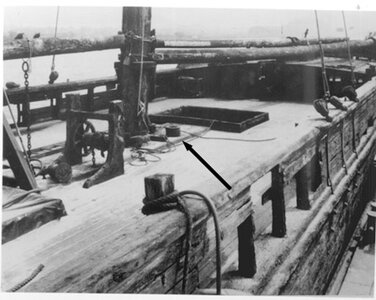

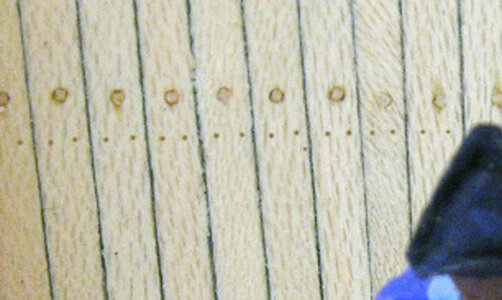

With the heavy planks in place at the bow the rest of the bulwarks can be planked. On this model four strakes of planking were run below the waterway molding. The sides and bottom of the hull are left open to show the framing. At the bow planks do not like to sit flat against the frames, they tend to spring up leaving a gap at the bottom edge. Planks not only have to bend around the bow but also twist to conform to the hull.

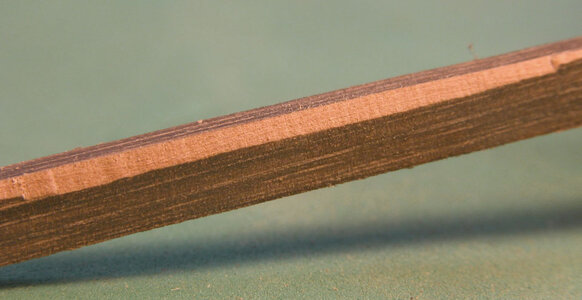

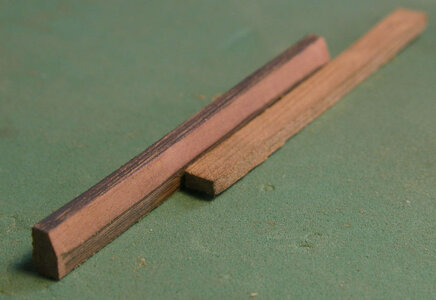

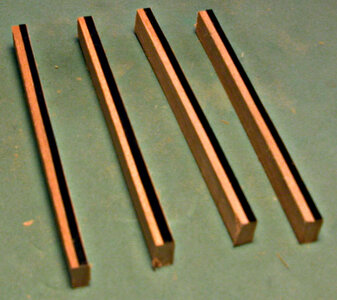

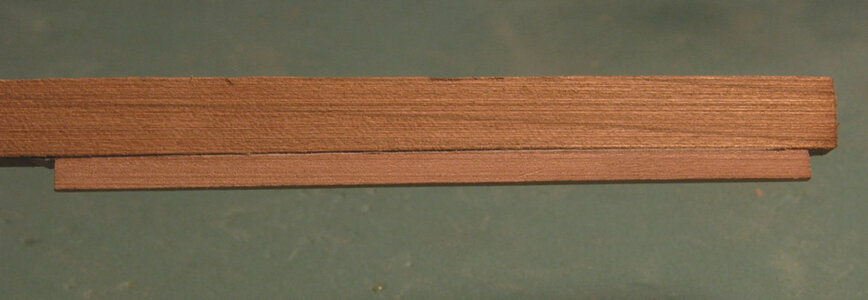

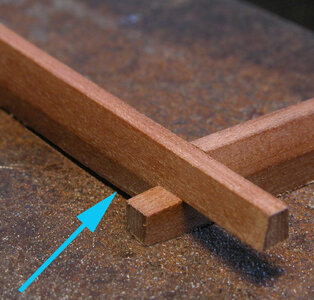

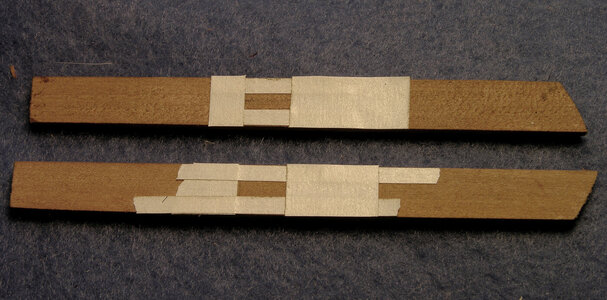

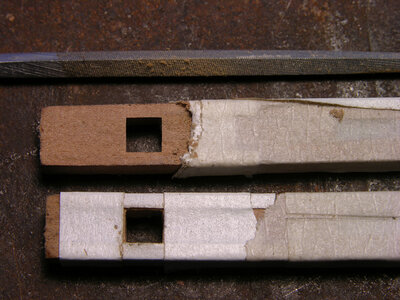

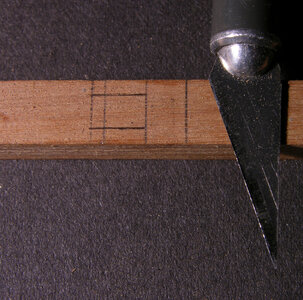

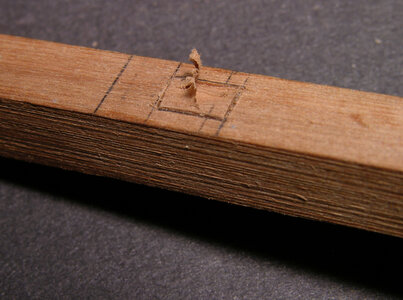

A method used to solve this problem is to use bevels and thickness tapers. To begin with the hull is planked in 3 inch thick Oak planks. At 1:48 scale that is .060, the planking has been milled .090 over size to allow for finishing and thickness tapers on the bow planks. If the plank is forced to lay flat against the frame, a gap will accrue between it and the plank above so a thickness taper is used. By using a single edge razor blade or sandpaper the inside face of the plank is shaped so the upper edge is slightly thinner than the bottom edge. Next a bevel is cut along the top edge of the plank.

By doing this it reduces the amount of twist needed to force the plank in place.

If you plan on planking the entire hull you can leave the gap and cover it with the next plank. By doing this a stepping is created and a hollow is left under the bottom of each plank. When the hull is sanded these planks will be paper thin. The thin planks will be affected by changes in humidity and shrink leaving a gap between planks.

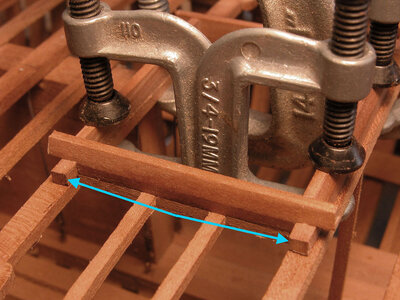

Using an edge bevel and thickness taper will not in itself correct the planking so it lays flat to the frame, it only aids in the difficulty of the bow planks to fall in place. Clamping is still needed to force the planks in place.

Soaking and steam bending will help bend and twist the planks. By soaking the planks to make them pliable also makes them soft and prone to being crushed and form dimples from the pressure of the clamp. Sometimes these dimples can be sanded out sometimes not.

In the construction of this model once again the planks were not steam bent or soaked in water. They were bent and twisted dry.

That sounds contrary to everything you hear about planking a hull. I have read many times of advice to soak a plank in water and use a hot bending tool. i have used steam bending in extreme cases like heavy wales but most of the time i will bend planks dry. First of all i scratch build models so i can select what wood to use. For planking that has to be bent i select woods that are naturally bendable, close grain and strong. It also has a lot to do with moisture content of the wood. Lumber for indoor use and the wood you get in kits are kiln dried to 6% to 8%. The drier the wood the more brittle it becomes. What i am using is air seasoned wood with a moisture of around 20%. I know what your thinking wood with such a high moisture will shrink and crack and that is true bring in a piece of lumber at 20% into the house at a dry 70 degrees it will indeed crack, warp and shrink. When i plan a project i work up a material list and cut planking first. By the time i get to it the wood has been laying around for a few months. Wood is hygroscopic leave it outdoors and it will accommodate to its surrounding. So wood at around 20% moisture bends much better than dry wood in a kit that might of been sitting a warehouse for months.

i live in a place where temperatures are drastic today it is Fahrenheit 3 Celsius -16 in a few days it will be Fahrenheit 50 Celsius 10

I have models that are 15 to 20 years old and as tight as the day i built them.