- Joined

- Sep 22, 2023

- Messages

- 173

- Points

- 143

Ciao a tutti i modellisti RC navali.

Piccolo passo indietro.

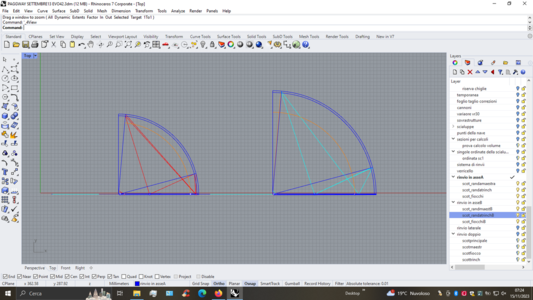

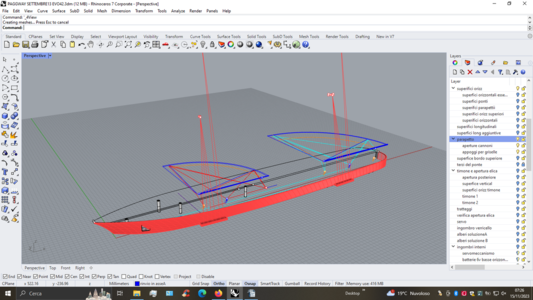

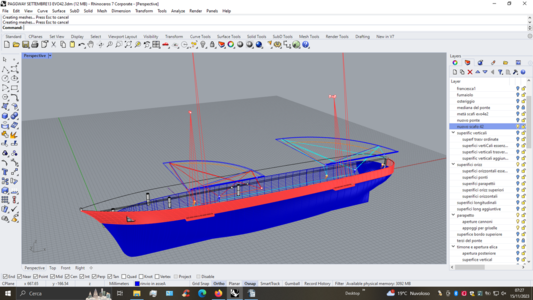

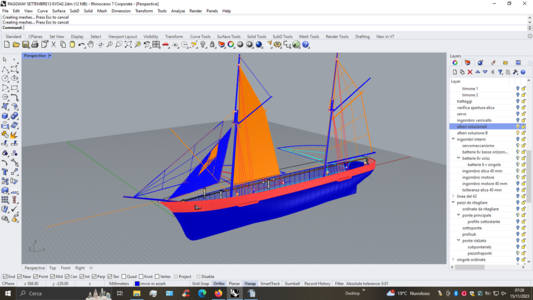

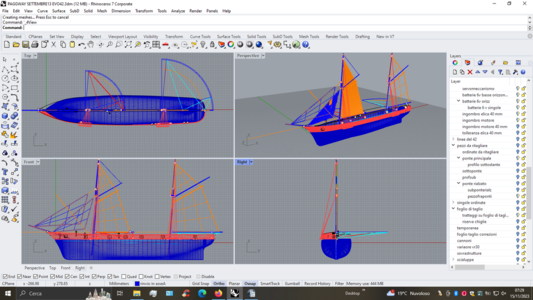

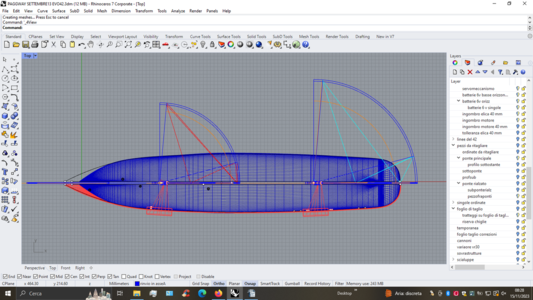

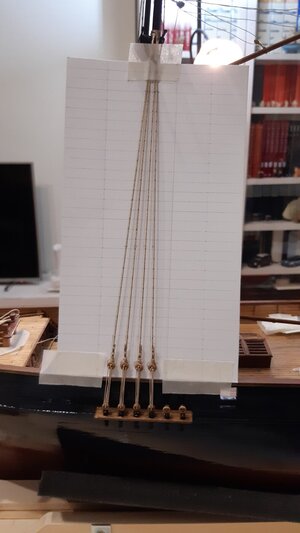

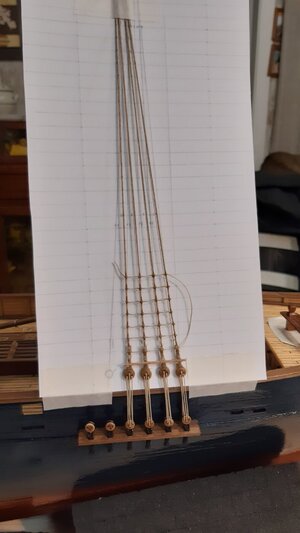

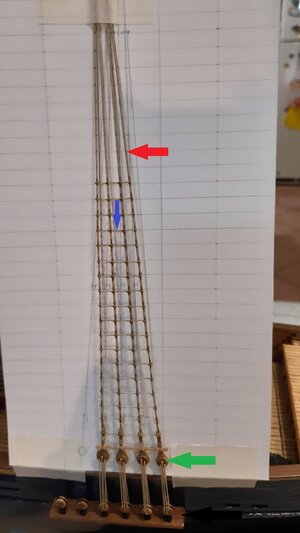

Quello che vi mostrerò nelle foto seguenti è il metodo che ho utilizzato per abbassare il più possibile il baricentro del modello.

I test in acqua che ho effettuato man mano che la costruzione procedeva mi hanno fatto capire che non avevo più molto margine.

La zavorra che avrei potuto aggiungere non era molta. Sicuramente non più di 450 grammi.

In generale, 5 kg di dislocamento sono pochissimi per un modello lungo più di un metro che deve manovrare sei vele con due winch.

Un centimetro sopra o sotto la linea di galleggiamento per i modelli di peso pari o superiore a 7 kg non ha molta importanza.

Non importa quasi nulla se non devono navigare a vela. Un centimetro in meno sul bordo libero del mio modello è una tragedia.

L'unico asso nella manica era la sostituzione delle batterie. Se avessi sbagliato qualcosa e quindi il peso complessivo fosse stato maggiore di quello autoimposto, avrei sostituito le due batterie AGM al piombo con altre tecnologie più leggere, recuperando fino a 700-800 grammi.

Per fortuna avevo sistemato molto bene la posizione delle batterie, del motore e di tutte le altre parti essenziali.

Senza zavorra il modello ha reagito con una leggera spinta raddrizzante alle forze che lo sbilanciavano lateralmente.

Nonostante la spinta non fosse forte si stava comunque raddrizzando e quindi sono partito da una buona base.

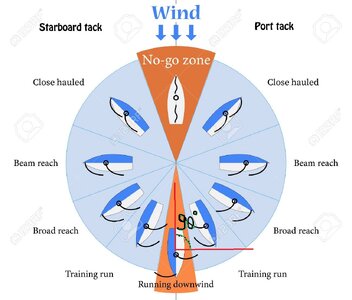

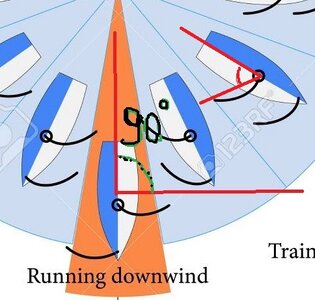

Avrei dovuto aggiungere zavorra per aumentare la spinta raddrizzante in previsione di sbandamento molto forte nelle navigazioni al traverso con vento forte. (vedi foto allegata delle velocità di navigazione)-

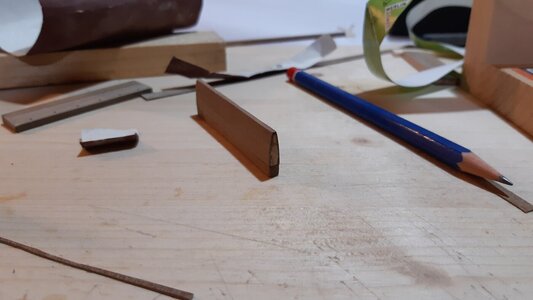

Il trucco è stato quello di sostituire la chiglia di legno con un prisma di ottone.

La riduzione, necessaria per poterlo rivestire meglio di mogano, ha interessato due dei quattro lati del prisma.

Originariamente la barra di ottone lunga 658 mm era 9x9 mm con la riduzione è diventata 8x9 mm.

Quello originale aveva un peso di 440 g. e la forza raddrizzante (non calcolata) era quella visibile nel filmato dedicato alla stabilità, il cui link è già stato inserito in questo topic.

Quello attuale pesa meno, siamo a 400 grammi. Non ci sono zavorre oltre a questa barra di ottone.

A quel punto dei lavori l'intero modello pesava 3162 grammi, a cui vanno aggiunti 1400 grammi delle due batterie e 90 grammi di elementi pronti da aggiungere per un totale non definitivo di 4652 grammi.

La barra di ottone viene avvitata allo scafo e ulteriormente bloccata con un finissimo strato di silicone.

La barra di ottone non è visibile né lateralmente né dal basso, perché è completamente rivestita da listelli di mogano.

Oltre ad una questione estetica, il mogano verniciato impermeabilizza la barra di ottone.

Perché ho scelto l'ottone?

L'ottone è una lega che pesa più del ferro ma meno del piombo.

Rispetto al ferro/acciaio è migliore sotto ogni punto di vista tranne quello del costo.

Infatti non arrugginisce come il ferro, pesa di più ed è facilmente lavorabile. In commercio si trovano profili in ottone molto diritti.

Rispetto al piombo è meno pesante ma molto più lavorabile, inoltre non si trovano profili di piombo quadrati così lunghi e diritti (almeno in Italia).

Meglio ancora, più pesante dell'ottone, dell'acciaio e del piombo, sarebbe stato l'oro, ma 400 grammi d'oro mi sarebbero costati troppo! ahahahahahah.

Hello to all naval RC modelers.

Small step back.

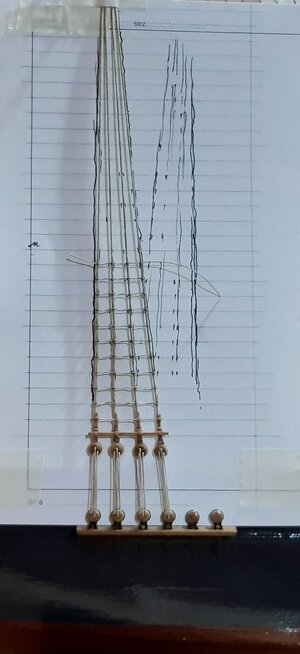

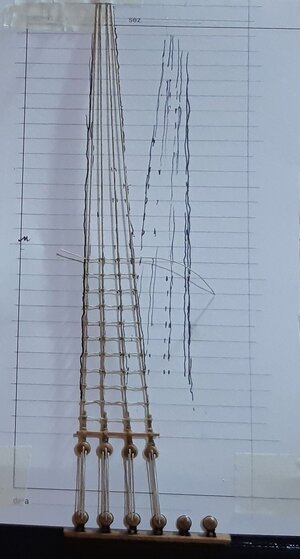

What I will show in the following photos is the method I used to lower the model's center of gravity as much as possible.

The water tests I carried out as the construction progressed made it clear to me that I no longer had much margin.

The ballast I could have added wasn't much. Definitely no more than 450 grams.

In general, 5 kg of displacement is very little for a model more than one meter long that must control six sails with two winches.

A centimeter above or below the waterline for models weighing 7 kg and above does not matter much.

It matters almost nothing if they don't have to sail with sails.

One centimeter less on the free edge of my model is a tragedy.

The only trick up the sleeve was replacing the batteries.

If I had done something wrong and therefore the total weight would have been greater than the self-imposed one, I would have replaced the two AGM lead batteries with other lighter technologies, recovering up to 700-800 grams.

Luckily I had arranged the position of the batteries, motor and all the other essential parts very well.

Without ballast the model reacted with a slight righting push to the forces that unbalanced it to the side.

Although the push wasn't strong it was still straightening and therefore I started from a good base.

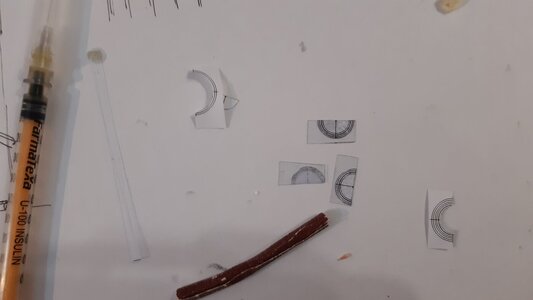

I should have added ballast in order to increase the righting thrust in anticipation of very strong heelings in Beam Reach sailings in strong winds. (see attached photo of sailing speeds)

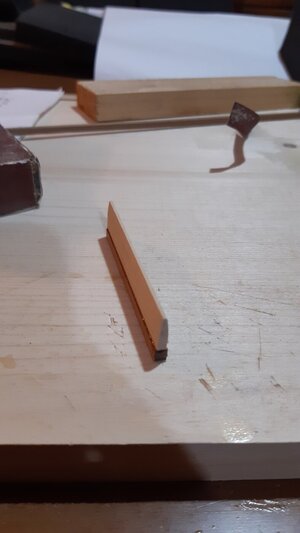

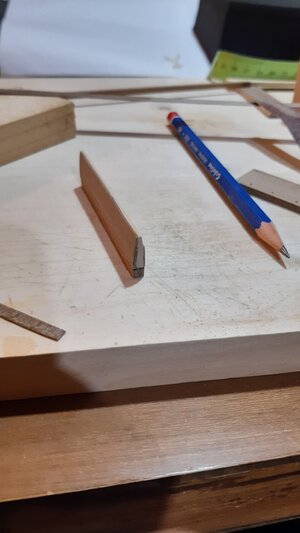

The trick was to replace the wooden keel with a brass prism.

The reduction, necessary to be able to veneer it better with mahogany, involved two of the four sides of the prism.

Originally the 658 mm long brass bar was 9x9 mm with the reduction it became 8x9 mm.

The original one had a weight of 440 g. and the straightening force (not calculated) was the one visible in the film dedicated to stability, the link to which has already been inserted in this post.

The current one weighs less, we are at 400 grams.

There are no ballasts other than this brass bar.

At that point of the work, the whole model weighed 3162 grams, to which must be added 1400 grams of the two batteries and 90 grams of elements ready to be added for a non-definitive total of 4652 grams.

The brass bar is screwed to the hull and further blocked with a very fine layer of silicone.

The brass bar is not visible either from the side or below, because it is completely covered with mahogany strips.

In addition to an aesthetic issue, the painted mahogany waterproofs the brass bar.

Why did I choose brass?

Brass is an alloy that weighs more than iron but less than lead.

Compared to iron/steel it is better from every point of view except cost.

In fact it does not rust like iron, it weighs more and is easily workable. Very straight brass profiles are found on the market.

Compared to lead it is less heavy but much more workable, furthermore you cannot find such long and straight square lead profiles (at least in Italy).

Best of all, heavier than brass, steel and lead, would have been gold but 400 grams of gold would have cost me too much! ahahahahahaha.

Piccolo passo indietro.

Quello che vi mostrerò nelle foto seguenti è il metodo che ho utilizzato per abbassare il più possibile il baricentro del modello.

I test in acqua che ho effettuato man mano che la costruzione procedeva mi hanno fatto capire che non avevo più molto margine.

La zavorra che avrei potuto aggiungere non era molta. Sicuramente non più di 450 grammi.

In generale, 5 kg di dislocamento sono pochissimi per un modello lungo più di un metro che deve manovrare sei vele con due winch.

Un centimetro sopra o sotto la linea di galleggiamento per i modelli di peso pari o superiore a 7 kg non ha molta importanza.

Non importa quasi nulla se non devono navigare a vela. Un centimetro in meno sul bordo libero del mio modello è una tragedia.

L'unico asso nella manica era la sostituzione delle batterie. Se avessi sbagliato qualcosa e quindi il peso complessivo fosse stato maggiore di quello autoimposto, avrei sostituito le due batterie AGM al piombo con altre tecnologie più leggere, recuperando fino a 700-800 grammi.

Per fortuna avevo sistemato molto bene la posizione delle batterie, del motore e di tutte le altre parti essenziali.

Senza zavorra il modello ha reagito con una leggera spinta raddrizzante alle forze che lo sbilanciavano lateralmente.

Nonostante la spinta non fosse forte si stava comunque raddrizzando e quindi sono partito da una buona base.

Avrei dovuto aggiungere zavorra per aumentare la spinta raddrizzante in previsione di sbandamento molto forte nelle navigazioni al traverso con vento forte. (vedi foto allegata delle velocità di navigazione)-

Il trucco è stato quello di sostituire la chiglia di legno con un prisma di ottone.

La riduzione, necessaria per poterlo rivestire meglio di mogano, ha interessato due dei quattro lati del prisma.

Originariamente la barra di ottone lunga 658 mm era 9x9 mm con la riduzione è diventata 8x9 mm.

Quello originale aveva un peso di 440 g. e la forza raddrizzante (non calcolata) era quella visibile nel filmato dedicato alla stabilità, il cui link è già stato inserito in questo topic.

Quello attuale pesa meno, siamo a 400 grammi. Non ci sono zavorre oltre a questa barra di ottone.

A quel punto dei lavori l'intero modello pesava 3162 grammi, a cui vanno aggiunti 1400 grammi delle due batterie e 90 grammi di elementi pronti da aggiungere per un totale non definitivo di 4652 grammi.

La barra di ottone viene avvitata allo scafo e ulteriormente bloccata con un finissimo strato di silicone.

La barra di ottone non è visibile né lateralmente né dal basso, perché è completamente rivestita da listelli di mogano.

Oltre ad una questione estetica, il mogano verniciato impermeabilizza la barra di ottone.

Perché ho scelto l'ottone?

L'ottone è una lega che pesa più del ferro ma meno del piombo.

Rispetto al ferro/acciaio è migliore sotto ogni punto di vista tranne quello del costo.

Infatti non arrugginisce come il ferro, pesa di più ed è facilmente lavorabile. In commercio si trovano profili in ottone molto diritti.

Rispetto al piombo è meno pesante ma molto più lavorabile, inoltre non si trovano profili di piombo quadrati così lunghi e diritti (almeno in Italia).

Meglio ancora, più pesante dell'ottone, dell'acciaio e del piombo, sarebbe stato l'oro, ma 400 grammi d'oro mi sarebbero costati troppo! ahahahahahah.

Hello to all naval RC modelers.

Small step back.

What I will show in the following photos is the method I used to lower the model's center of gravity as much as possible.

The water tests I carried out as the construction progressed made it clear to me that I no longer had much margin.

The ballast I could have added wasn't much. Definitely no more than 450 grams.

In general, 5 kg of displacement is very little for a model more than one meter long that must control six sails with two winches.

A centimeter above or below the waterline for models weighing 7 kg and above does not matter much.

It matters almost nothing if they don't have to sail with sails.

One centimeter less on the free edge of my model is a tragedy.

The only trick up the sleeve was replacing the batteries.

If I had done something wrong and therefore the total weight would have been greater than the self-imposed one, I would have replaced the two AGM lead batteries with other lighter technologies, recovering up to 700-800 grams.

Luckily I had arranged the position of the batteries, motor and all the other essential parts very well.

Without ballast the model reacted with a slight righting push to the forces that unbalanced it to the side.

Although the push wasn't strong it was still straightening and therefore I started from a good base.

I should have added ballast in order to increase the righting thrust in anticipation of very strong heelings in Beam Reach sailings in strong winds. (see attached photo of sailing speeds)

The trick was to replace the wooden keel with a brass prism.

The reduction, necessary to be able to veneer it better with mahogany, involved two of the four sides of the prism.

Originally the 658 mm long brass bar was 9x9 mm with the reduction it became 8x9 mm.

The original one had a weight of 440 g. and the straightening force (not calculated) was the one visible in the film dedicated to stability, the link to which has already been inserted in this post.

The current one weighs less, we are at 400 grams.

There are no ballasts other than this brass bar.

At that point of the work, the whole model weighed 3162 grams, to which must be added 1400 grams of the two batteries and 90 grams of elements ready to be added for a non-definitive total of 4652 grams.

The brass bar is screwed to the hull and further blocked with a very fine layer of silicone.

The brass bar is not visible either from the side or below, because it is completely covered with mahogany strips.

In addition to an aesthetic issue, the painted mahogany waterproofs the brass bar.

Why did I choose brass?

Brass is an alloy that weighs more than iron but less than lead.

Compared to iron/steel it is better from every point of view except cost.

In fact it does not rust like iron, it weighs more and is easily workable. Very straight brass profiles are found on the market.

Compared to lead it is less heavy but much more workable, furthermore you cannot find such long and straight square lead profiles (at least in Italy).

Best of all, heavier than brass, steel and lead, would have been gold but 400 grams of gold would have cost me too much! ahahahahahaha.