.

Ab, I am very sorry that you found the substance of my explanations disappointing. However, this way works in practice, and a substantive discussion with arguments of the "no because no" kind is simply not possible. Escher's drawings obviously have nothing to do here, and to contrast attractive form and correctness of the solution is not quite fair. Would this also mean that all your wonderful creations are worthless in terms of their historical reliability? Indeed, it would probably be best for you to present your own, alternative interpretation of this line, instead of suggesting the opposite and vague at the same time in an unspecific way that explains nothing.

Nonetheless, in accordance with your wish, I offer additional clarification below.

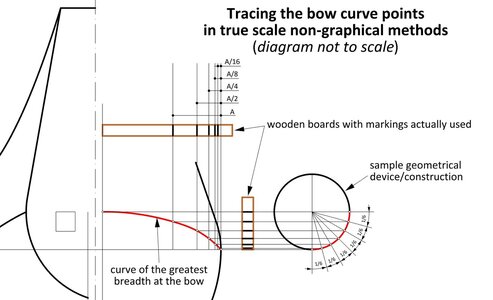

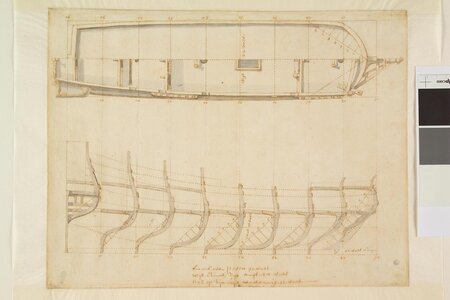

First of all, the method I have presented is very closely related to the essence of the bottom-first method, known from Witsen's descriptions, and actually follows directly from it.

Secondly, the contours of the frames obtained in this way agree very well with the contours of Rålamb's frames (you can check it yourself).

Thirdly, it is a mistaken assumption that the transverse strings/lattices would interfere with the work, as they did not have to be permanently mounted, but only applied for a moment to check the shapes obtained.

Fourthly, similarly, in the context of the possible obstruction by these longitudinal guides, one may associate them with scaffolding on the building construction sites. They, too, obstruct access to the façade to a certain extent, but are nevertheless always used.

Fifthly, the side guides outside the constructed hull I show, could in practice be both precisely set according to pre-calculated co-ordinates by the most rigorous shipwrights, but could equally well be set by eye by those less formalistic workers, giving almost equally good results. All that was really needed was for them to be more or less symmetrical, and their run in a generally correct manner, and even without much precision it was probably possible to build a somehow-floating hull. In this sense, it's a very practical, versatile method with the potential for widespread, convenient use.

Sixthly, what rule-of-thumbs are you talking about? I have just now demonstrated such a rule-of-thumb working in practice. Because it is not about the width of the flat at all, which is easily controlled by the obvious measuring, but its correct angle, variable along the length of the hull, which is much harder to control without this guide. The width of the flat and its inclination are two different things.

And one more general remark. The applied mathematical operations are so simple in this case, and the amount of resulting data (numbers) is so small that they could really be easily remembered or recalculated in the head on the spot, even without any abacuses or drawing these lines on paper. A person incapable of these simplest arithmetic calculations would also be completely helpless and incapable of independent living at all. Although I've heard that the Amazon Indians can only count to three, any number greater than that is "a lot."

.

.

.