.

This is only the beginning of the work on Witsen's pinas, but somehow I feel that in this particular case the statement of Peter I, who, after learning shipbuilding in the Netherlands and later in England for months, would be appropriate: 'If I had contented myself with learning the art of shipbuilding in Holland, I would only have become a ship carpenter [and not a ship designer].' However, perversely, this was apparently not because Dutch shipwrights, at least some of them, were incapable of designing ships in an engineering way, but rather because they simply did not see fit to share this knowledge with the Russian ruler.

In quite the same way, as it now appears, they did not see fit to enlighten Witsen on the matter either, and if he was paying for the information, it is fair to say that he was cheated, so to speak. He was told almost 'everything': general hull shape requirements for different types of vessels, more or less simplified construction procedures, most typical proportions of ship dimensions and structural elements, etc., he was even allowed to measure ships and their parts in the shipyard (all also invaluable information today), but the most important thing – how to design ships in a conceptual sense – was denied to him.

For, unlike common ships like boxy fluits and the like, with their extremely simple design concept, the pinas Witsen describes begins to appear as a rather sophisticated design for its era, already requiring a plan on paper beforehand.

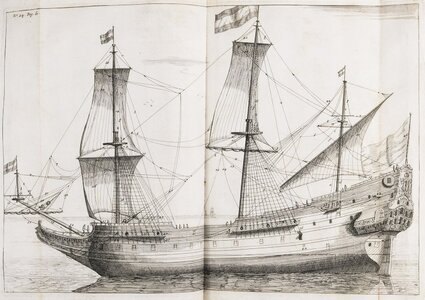

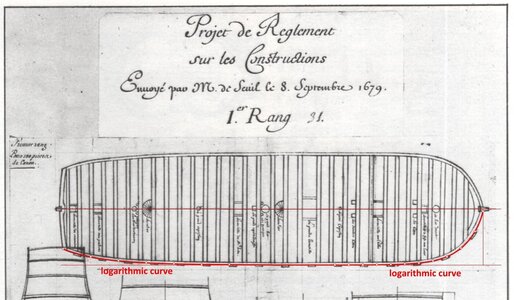

General view of the pinas in Witsen's monumental work Aeloude en hedendaegsche scheeps-bouw en bestier, 1671:

Witsen has included in his work the detailed dimensions of the various parts of the pinas and the co-ordinates of the distinctive hull lines appearing at the various stages of her construction as well, which makes it possible to attempt to reconstruct the shape of this ship, but even more interestingly, perhaps it will also make it possible to reconstruct her design concept. The necessary data can be found not only in Witsen's work itself, but also in the excellent book Nicolaes Witsen and Shipbuilding in the Dutch Golden Age by Ab Hoving.

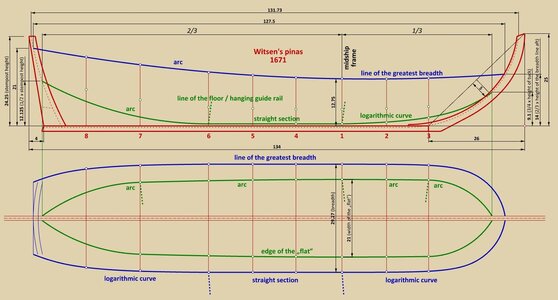

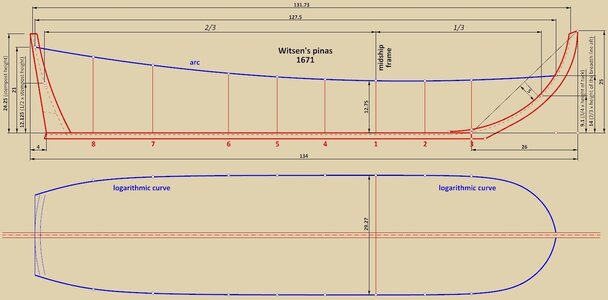

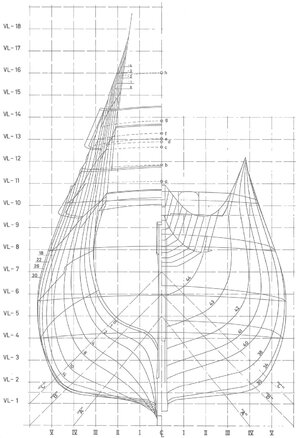

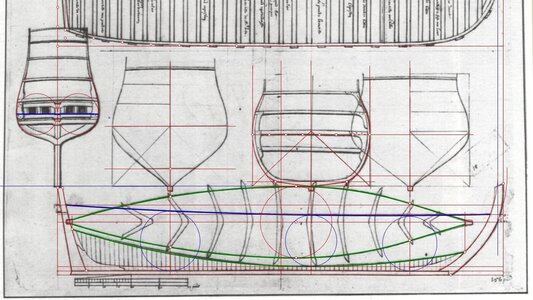

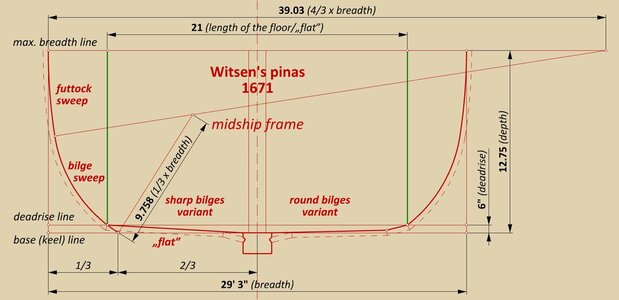

The reconstructed main proportions of the ship and the run of the line of greatest breadth (scheergang, scheerstrook), in blue, are shown below. The points on this line visible in the diagram are its coordinates measured by Witsen himself or his assistant. In the side view this line has the shape of an arc of a circle, and in the top view it is a logarithmic curve for both ends of the hull.

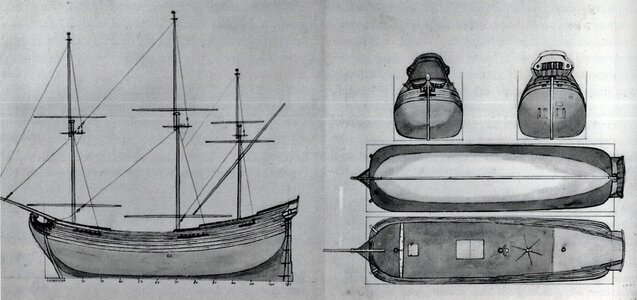

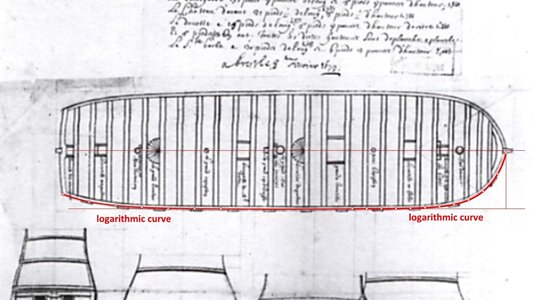

As a kind of a parallel, logarithmic curves were also used to form the line of greatest breadth by shipwrights of Dutch origin in the French service, Laurent and Étienne Hubac, in their chronologically not-too-distant designs of 1679:

Dimensions of the pinas' hull:

Length between posts: .................................... 134 feet

Length between rabbets: ................................ 131.73 feet

Horizontal length of the line

of greatest breadth: .......................................... 127.5 feet

Breadth: .................................................................... 29 feet 3 inches (length between rabbets / 4.5)

Depth (height of design grid

from keel to the line of greatest

breadth at midship frame): .............................. 12.75 (1/10 x horizontal length of the line of greatest breadth)

Longitudinal position of the frame #1

(most likely the midship frame): ....................... 1/3 of the horizontal length of the line of the floor.

The remaining dimensions are included in the diagram (note: this is a work-in-progress, so some details may change, which will be indicated).

.

Last edited:

?

?