- Joined

- Sep 22, 2023

- Messages

- 173

- Points

- 143

Grazie mille per i complimenti, Peter.Very impressive project. I like the idea that you didn’t give up when faced with a challenge.

Thanks so much for the compliments, Peter.

Grazie mille per i complimenti, Peter.Very impressive project. I like the idea that you didn’t give up when faced with a challenge.

Grazie ancora Peter.I wish I’d known about this tool 35 years ago when I built my only plank on frame model boat. I opted for building plastic models after that, only because my career got more involved and I didn’t have the time to devote. I’ve got so much respect for the craftsmanship of the members on here.

Grazie mille Tobias.Hi Alessandro this is fantastic work you have done so far.

Ciao Johan e Shota70, vi ringrazio ancora una volta per i vostri graditi apprezzamenti.A very thorough and methodical approach to a seamingly insignificant part. My compliments.

Hello Alessandro,Ciao Johan e Shota70, vi ringrazio ancora una volta per i vostri graditi apprezzamenti.

Tuttavia, il timone è una parte essenziale per il modellista RC a vela.

Mi spiego meglio, sperando di fare una traduzione comprensibile.

Il mio problema potrebbe essere navigare esclusivamente con vento, a basse velocità. Potrebbe essere.

Nella navigazione a motore non ci sono problemi. Il flusso dell'acqua direttamente sull'elica rende efficace qualsiasi timone.

Non ho mai visto nessun modellista RC motorizzato avere problemi di rotazione. Non esiste come problema.

Il problema riguarda le navi a vela.

I modellisti RC a vela utilizzano timoni sovradimensionati. Troppo sovradimensionati per essere realistici.

Se io riesco ad andare a vela ma poi non riesco a virare senza usare l'elica, considero fallito uno dei miei obiettivi.

Hi Johan and Shota70, thank you once again for your kind comments.

However, the rudder is an essential part for the sailing RC modeler.

Let me explain better, hoping to make an understandable translation.

My problem could be sailing exclusively with wind, at low speeds. Could be.

In motor navigation there are no problems.

The flow of water directly onto the propeller makes any rudder effective.I have never seen any motorized RC modeler have rotation problems.

It doesn't exist as a problem.

The problem concerns sailing ships.

Sailing RC modelers use oversized rudders. Too oversized to be realistic.

If I manage to sail but then I can't turn without using the propeller, I consider one of my goals to have failed.

Ciao Johan.Hello Alessandro,

It is my understanding of sailing large ships (under sail) that the main heading is controlled by the sails, not the rudder. The rudder is used for small course corrections. Even on small sailing boats the jib is used to go through the wind. The manoeuvre is controlled by the rudder, but the jib energizes the turn.

Making a larger than necessary/defined rudder will make an RC ship turn faster, but it remains to be seen whether or not that's really necessary.

Morning Alessandro,Ciao Johan

"The manoeuvre is controlled by the rudder, but the jib energizes the turn."

Tu che intendi per "turn"?

Te lo chiedo perchè non vorrei fare confusione capendo male.

Faccio una premessa:

In italiano abbiamo due termini: "virata" e "abbattuta" (o più impropriamente "strambata"). Sono entrambi cambi di direzione e cambi di mure.

In realtà i cambi di direzione sono quattro:

orzare = to luff, to haul the wind, to go windward

poggiare = to bear away Dirigere l'imbarcazione allontanando la prua dalla direzione di provenienza del vento, in modo da navigare con un'andatura più "larga", cioè con le vele più "lasche". E' il contrario di "orzare".

virare = to tack, to go about. Detto anche semplicemente virare, è il manovrare di un veliero per portarlo da una andatura di bolina all'analoga sul bordo opposto, passando con

la prua dalla direzione controvento. La manovra si effettua "orzando" al massimo mantenendo la velocità, portando

quindi la barra "sottovento" e recuperandola al centro dopo il cambio di mura.

abbattere/strambare = to gybe, to wear. Usato comunemente per indicare su un veliero l'insieme delle manovre

per virare di bordo in poppa.

Lasciando predere le prime due perche non c'è cambio di mure, nella virata il veliero (qualsiasi nave a vela) passa per un angolo morto.

In quest'angolo si va contro vento entro i massimi gradi consentiti dalla bolina stretta, perciò tutte le vele (compresi i fiocchi) non sono in grado di prendere vento e sostenere la manovra. E' solo il timone che fa tutto e la manovra riesce solo se c'è sufficiente abbrivio (course, run, headway), agendo molto velocemente per cambiare mure alle vele.

Spero che qualcosa si sia capito con la mia pessima traduzione.

Hi Johan.

"The maneuver is controlled by the rudder, but the jib energizes the turn."

What do you mean by "turn"?

I'm asking because I don't want to cause confusion by misunderstood.

I'll make a premise:

In Italian we have two terms: "virata" and "abbattuta" (or more improperly "strambata").

They are both changes of direction and changes of tack.

In reality there are four changes in direction:

orzare = to luff, to haul the wind, to go windward

puggiare = to bear away Steering the boat by moving the bow away from the direction of the wind, so as to sail with a "wider" gait, i.e. with "looser" sails. It is the opposite of "luff".

virare = to tack, to go about.

Also known simply as tacking, it is the maneuvering of a sailing vessel to take it from a close-hauled position to a similar one on the opposite edge, passing withthe bow from the upwind direction. The maneuver is carried out by "luffing" to the maximum while maintaining speed, carryingthen the "leeward" bar and recovering it to the center after the change of tack.

abbattere/strambare: to gybe, to wear. Commonly used to indicate the set of maneuvers on a sailing shipto tack downwind.

Leaving the first two to be taken because there is no change of tack, in the tack ("virata") the sailing ship (any sailing ship) passes through a dead corner.

In this corner you are going into the wind within the maximum degrees allowed by close hauling (bowline, Up wind), so all the sails (including the jibs) are unable to catch the wind and support the maneuver.

It is only the rudder that does everything and the maneuver is only successful if there is sufficient headway (course, run, headway), acting very quickly to change sail tack.

I hope something was understood with my terrible translation.

Ciao Johan, buongiorno.Morning Alessandro,

I was mainly referring to "go about", but also on other ways to change coarse or to go windward or the opposite direction, it will be a combination of managing the sheets, to tighten or to loosen the sails, supported by corresponding rudder deflections.

You're absolutely right, when tacking, there's that moment you're dead into the wind, so at that point you need sufficient momentum in order to be able to complete the maneuver. I was taught to keep the jib on the "wrong side" of the mast, when going through the "dead zone" and only to tighten the other sheet once being positively gone about.

While writing this, I realized that momentum is involved when tacking; a RC modelship has a relatively low momentum. This might explain why rudder on RC models are larger than their full scale counterparts. Another issue might be that, and I don't whether or not this applies to RC ships as well, but no doubt someone will know, scaling down airfoils for aircraft does not result in similar flight characteristics, due to the changing Reynolds number ( which is, amongst others, determined by the chord of the body).

Good morning Alessandro,Ciao Johan, buongiorno.

Sono d'accordo con te su tutto. Voglio fare solo una precisazione, perchè sentendo citare il numero di Reynolds, mi sono reso conto che sto fuorviando involontariamente il discorso.

Ho paura di aver involontariamente portato chi legge su una via sbagliata.

Cerco di spiegarmi meglio:

Il profilo alare nei timoni non è un requisito richiesto, almeno non sempre.

Molti timoni, sono semplici pale (non profili alari biconvessi) e funzionano benissimo nei modelli a motore e nelle navi a vela vere.

L'idea di creare un profilo alare invece di una pala, è una mia fissazione.

L'idea mi è venuta nell'ipotesi (o nella speranza) che ciò avrebbe incrementato le prestazioni del timone.

Ipotizzavo (o speravo) che la portanza creata dal profilo alare del timone si aggiungesse alla spinta del deflusso di acqua (creato anche da una semplice pala).

Logicamente la portanza aumenta al quadrato della velocità.

Con un'elica attiva la velocità relativa (sottolineo relativa) sul timone è molto maggiore ed è presente anche se la nave è ferma.

L'idea di usare un profilo alare (nelle mie ipotesi) doveva compensare un ingrandimento esagerato del timone (che ho voluto evitare per motivi estetici).

Spero di non aver fatto ancora più confusione. Non rinunciare a discutere con me, anche se ne avresti tutti i motivi, ahahahahahah!

Parlando poi in generale e non specificatamente del timone.

Ci sono notevoli differenze fra modelli e navi vere. Sembra scontato ma non tutti sanno precisamente dov'è la differenza principale.

Nel film "Il volo della Fenice" del 1964, ma anche nel remake del 2004, l'ingegnere aeronautico di modelli in scala, risponde indignato al pilota: "non costruisco giocattoli ma modelli funzionanti in scala".

Afferma che gli stessi principi fisici che si applicano agli aerei veri si applicano ai modelli in scala.

Questo è verissimo e vale anche per i modelli navali ma c'è da considerare il "fattore di scala".

Qui nasce il grosso problema.

Riprodurre fedelmente un galeone o un vascello e cercare di farlo rimanere stabile in acqua, senza che si rovesci, è difficilissimo, perchè le misure lineari si riducono con rapporto 1:1, le superfici si riducono al quadrato e i volumi si riducono al cubo.

Questo cambia tutti i valori e i punti di riferimento (baricentro, centro di carena, metacentro, ecc. ecc.) in gioco.

Hi Johan, good morning.

I agree with you on everything.

I just want to make a clarification, because hearing the Reynolds number mentioned, I realized that I am involuntarily misleading the discussion.

I am afraid that I have unintentionally led the reader down the wrong path.

I'll try to explain myself better:

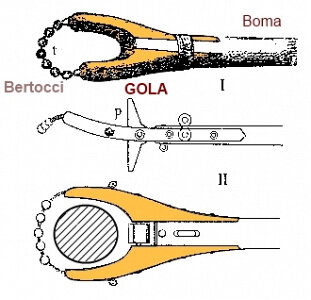

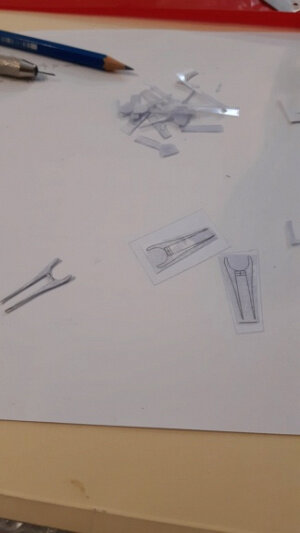

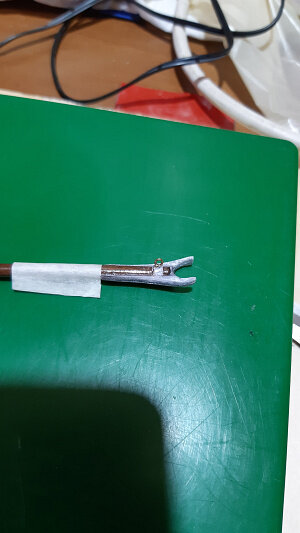

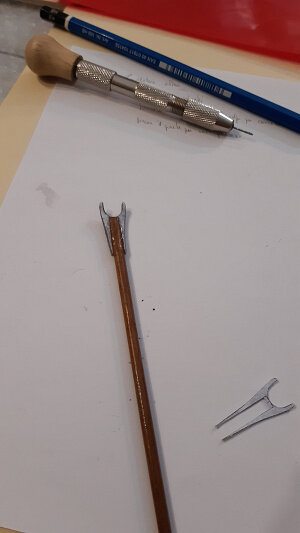

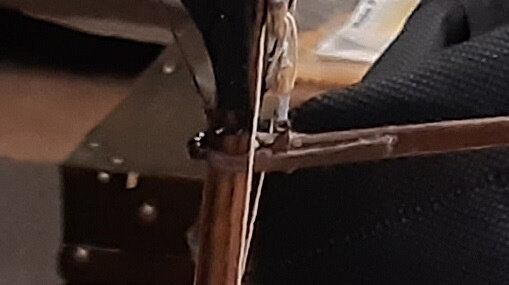

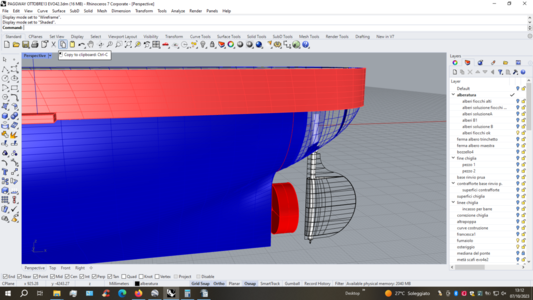

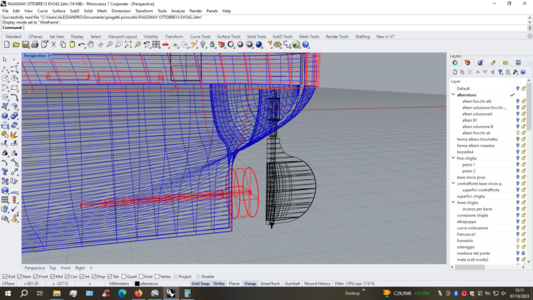

The airfoil in the rudders is not a requirement, at least not always.

Many rudders are simple blades (not biconvex airfoils) and work very well in motor models and real sailing ships.

The idea of creating an airfoil instead of a blade is an obsession of mine.

The idea came to me in the hypothesis (or hope) that this would increase the performance of the rudder.

I hypothesized (or hoped) that the lift created by the rudder's airfoil added to the thrust of the water outflow (created even by a simple blade).

Logically, lift increases as the square of speed.

With an active propeller the relative speed (I emphasize relative) on the rudder is much greater and is present even if the ship is stationary.

The idea of using an aerofoil (in my hypotheses) had to compensate for an exaggerated enlargement of the rudder (which I wanted to avoid for aesthetic reasons).

I hope I haven't made more confusion. Don't give up arguing with me, even if you have every reason to, ahahahahahah!

Then speaking in general and not specifically about the rudder.

There are notable differences between models and real ships.

It seems obvious but not everyone knows precisely where the main difference is.

In the 1964 film "The Flight of the Phoenix", but also in the 2004 remake, the scale model aeronautical engineer responds indignantly to the pilot: "I don't build toys but working scale models".

He claims that the same physical principles that apply to real airplanes apply to scale models.

This is very true and also applies to naval models but there is the "scale factor" to consider.

Here comes the big problem.

Faithfully reproducing a galleon or a vessel and trying to make it remain stable in the water, without capsizing, is very difficult, because the linear measurements are reduced with a 1:1 ratio, the surfaces are reduced to the square and the volumes are reduced to the cube.This changes all the values and reference points (center of gravity, center of hull, metacenter, etc. etc.) in play.