.

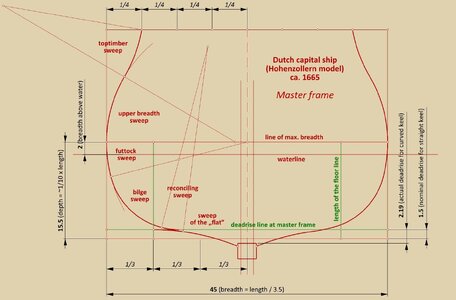

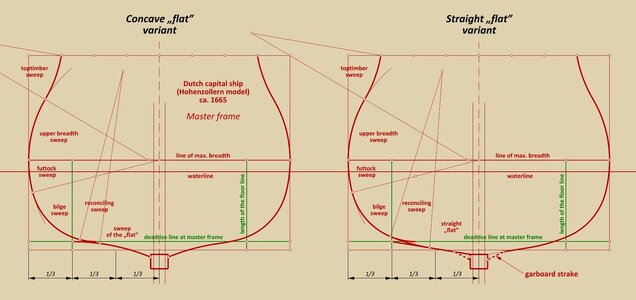

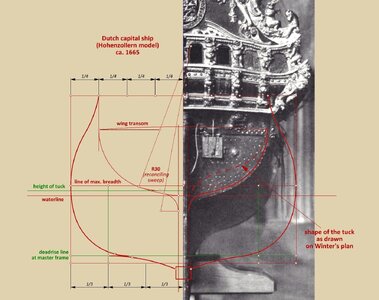

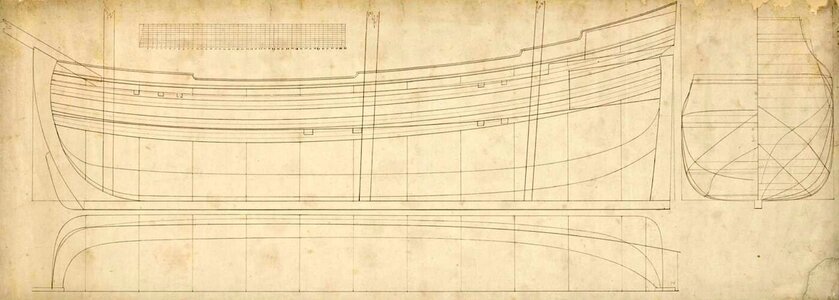

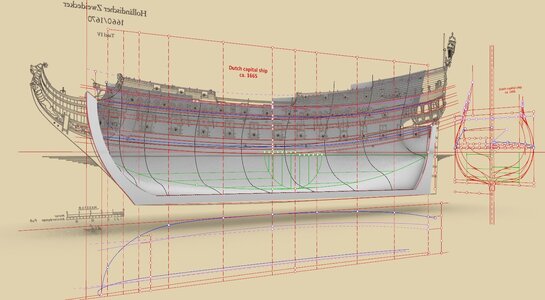

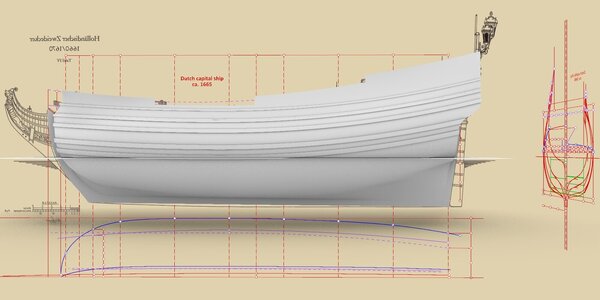

The basis for the analysis of the design method is a retrospective plan of a unique mid-17th century model of a Dutch warship, the so-called Hohenzollern model, made by taking its lines by Heinrich Winter, and published in his invaluable work Der holländische Zweidecker von 1660/1670. Nach dem zeitgenössischen Modell im ehemaligen Schloß Monbijou zu Berlin. The model itself was destroyed many decades ago, so repeating and verifying the process he performed with today's much more precise technology is no longer possible. Hence, by necessity, the present analysis must exceptionally be carried out on these modern interpreted data and not, as it should be, directly on the original source material.In parallel, the conceptual analysis of the Hohenzollern model 1660/70 is performed in almost obligatory conjunction with the analysis of the plans and numerical data of the nearly conceptually identical ships Prins Carl & Prins Wilhelm 1696, designed in 1695 by Ole Judichær, taken directly from the precious Danish archives, and also from the paper Nordeuropæisk spanteopslagning i 1500- og 1600-tallet. Belyst ud fra danske kilder by Niels Probst, [in:] Maritim Kontakt 16/1993, pp. 30–35.

Perhaps it is somewhat too early to post, nevertheless, something is already beginning to emerge from the chaos of the various present-day misrepresentations that can be shown. On the other hand, I am not yet quite sure that this analysis can be brought to a successful conclusion, yet, by starting this thread, there is a better chance of its completion.

In the context of state-of-the-art design concepts of Dutch warships, however, it can already be said that the results, even if partial, may significantly complement the information provided in 17th-century Dutch works on shipbuilding; as it happens – one work written by a more shipwright-carpenter than a shipwright-designer, and the other by a diplomat and official who was not told everything by professionals or who inappropriately chose his source of information.

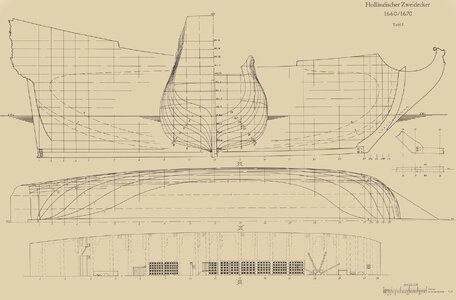

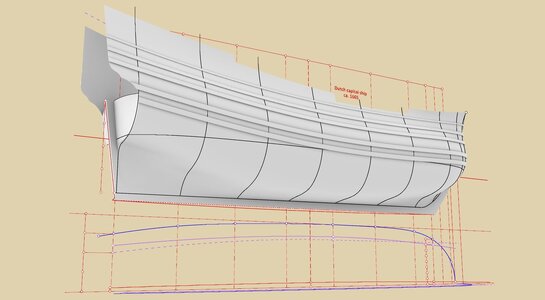

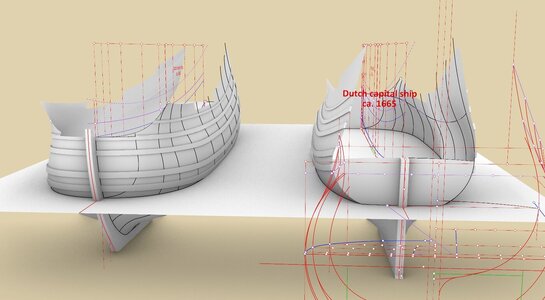

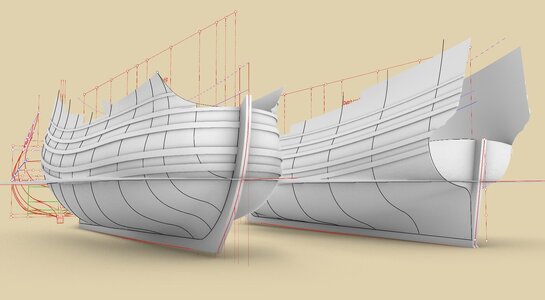

Lines plan of the model drawn up by Winter:

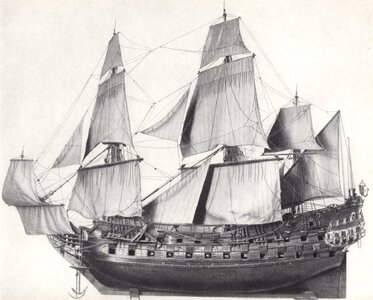

... and some of its photographs:

.

Last edited: