- Joined

- May 1, 2023

- Messages

- 112

- Points

- 113

Hi everyone!

I recently had the chance to visit Barcelona, and naturally, I made a stop at the Maritime Museum (MMB).

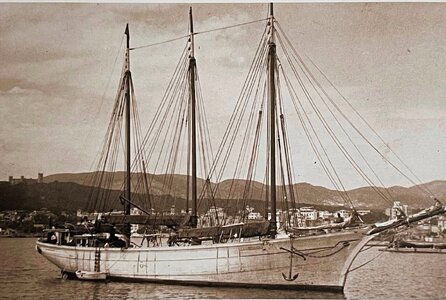

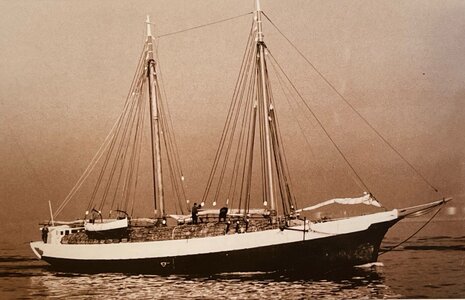

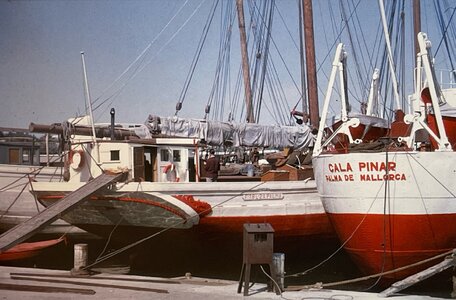

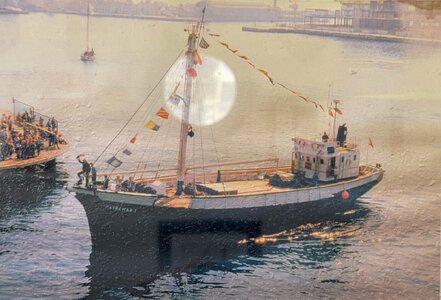

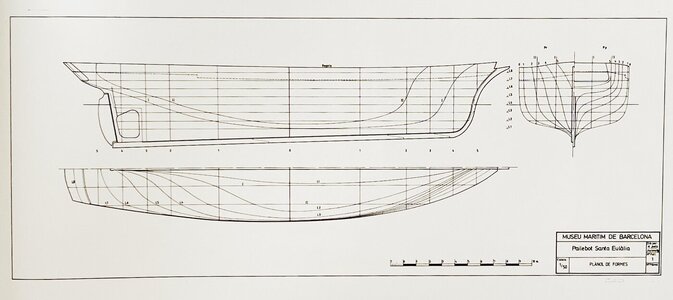

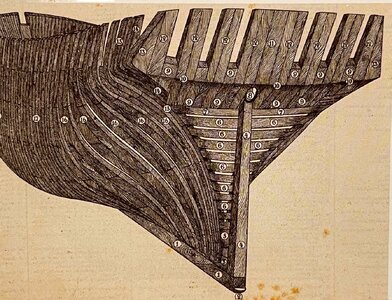

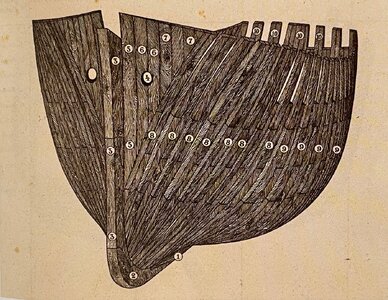

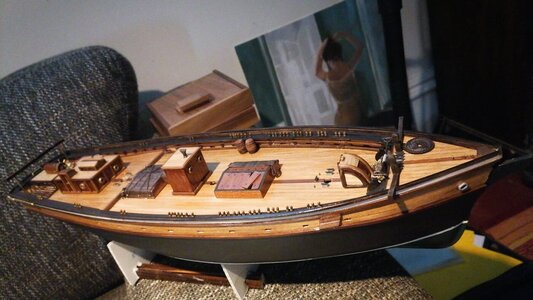

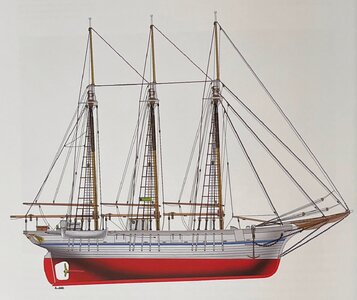

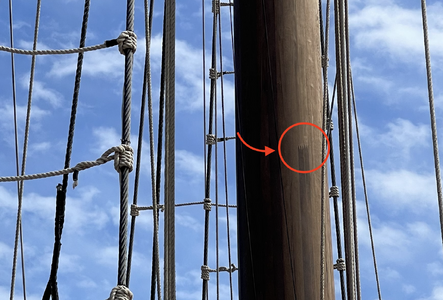

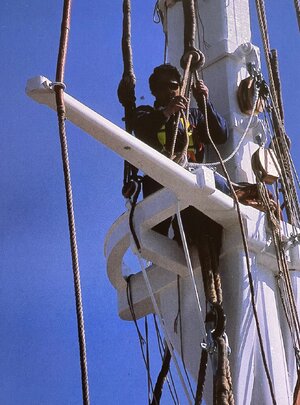

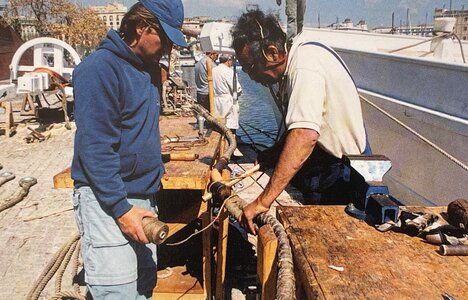

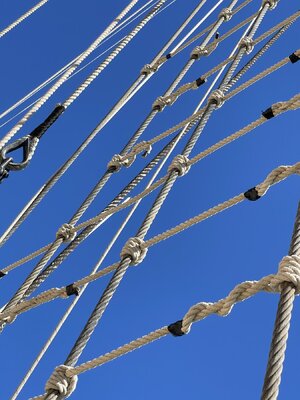

Many of you may already know that the three-masted schooner Santa Eulàlia is a gem in the MMB collection.

At least, It’s been a topic of discussion on SoS before. For me, the ship was an entirely new discovery.

Despite the limited time, I was determined to learn as much as possible about the ship from a ship modeler's perspective.

In museums, I always value the authenticity of actual artifacts over replicas or models, no matter how realistic they may seem.

This is precisely what makes Santa Eulalia so special.

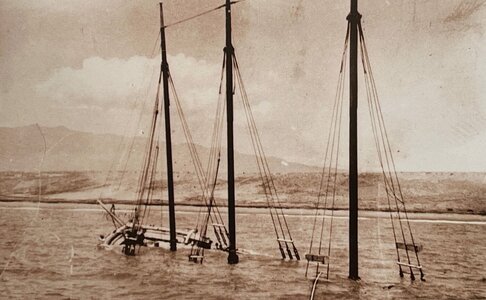

Originally launched as "Carmen Flores" in January 1919, she was built as a sailing vessel and operated under sail during her early years.

She stands as one of the last vessels of her era before the dawn of motorization.

That’s precisely what drew me to her. Here, I was able to see and feel all the elements of her construction and rigging that comprise the 'sailing spirit' of the ship.

I took some photos for personal reference, but I'm delighted to share them with you.

Even if you don't plan to model this specific ship, I believe the images could serve as valuable references for any shipbuilding projects from that era and category.

For better navigation here is the content of the thread:

1. A bit of history

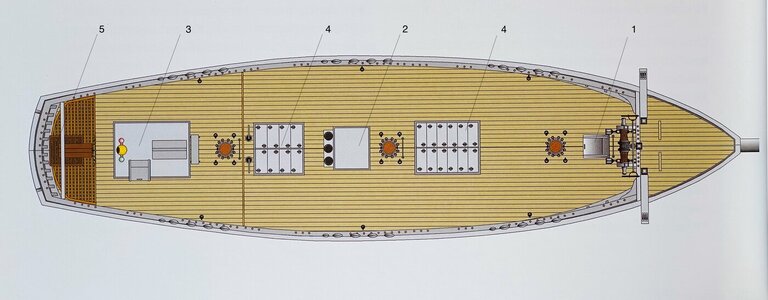

2. The hull

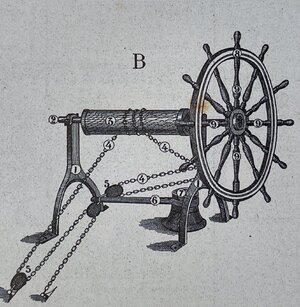

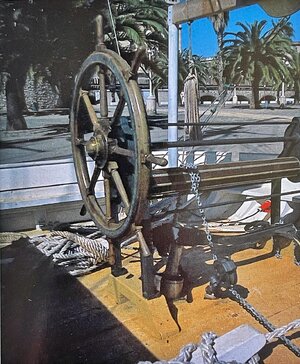

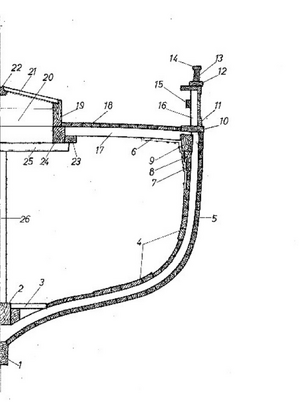

3. The steering mechanism

4. A short video

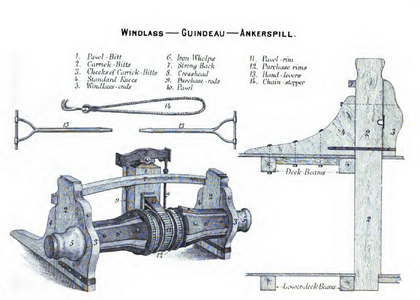

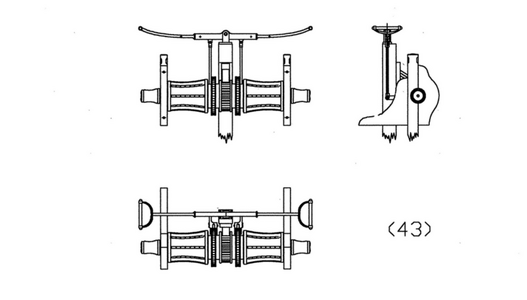

5. The Windlass

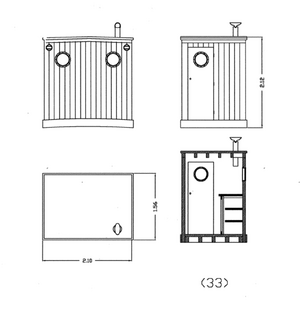

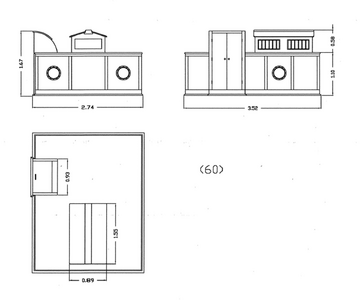

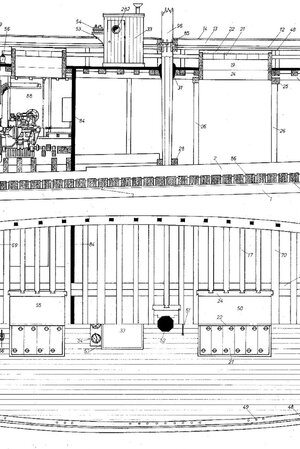

6. Superstructures on the deck - the bow hood, the galley and captain's cabin

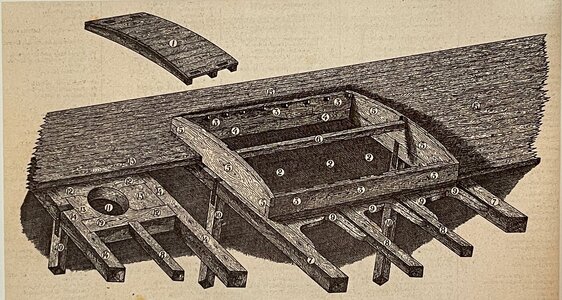

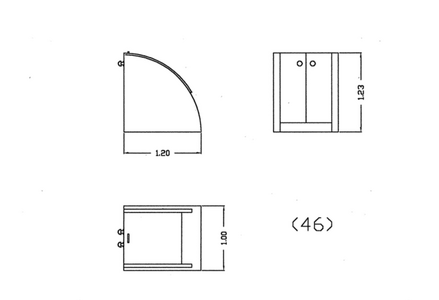

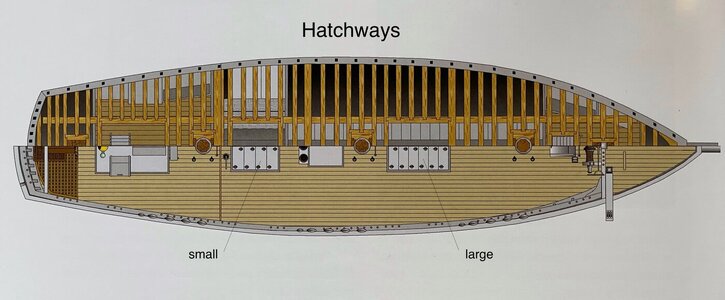

7. Superstructures on the deck - hatchways

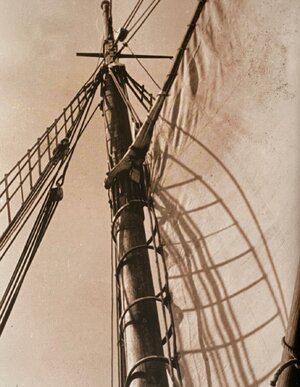

8. Masts

9. Rigging: ropes and blocks

10. Rigging: channels, dead-eyes, gaff and driver boom

11. Sails

12. The anchoring

13. ... to be continued

I recently had the chance to visit Barcelona, and naturally, I made a stop at the Maritime Museum (MMB).

Many of you may already know that the three-masted schooner Santa Eulàlia is a gem in the MMB collection.

At least, It’s been a topic of discussion on SoS before. For me, the ship was an entirely new discovery.

Despite the limited time, I was determined to learn as much as possible about the ship from a ship modeler's perspective.

In museums, I always value the authenticity of actual artifacts over replicas or models, no matter how realistic they may seem.

This is precisely what makes Santa Eulalia so special.

Originally launched as "Carmen Flores" in January 1919, she was built as a sailing vessel and operated under sail during her early years.

She stands as one of the last vessels of her era before the dawn of motorization.

That’s precisely what drew me to her. Here, I was able to see and feel all the elements of her construction and rigging that comprise the 'sailing spirit' of the ship.

I took some photos for personal reference, but I'm delighted to share them with you.

Even if you don't plan to model this specific ship, I believe the images could serve as valuable references for any shipbuilding projects from that era and category.

For better navigation here is the content of the thread:

1. A bit of history

2. The hull

3. The steering mechanism

4. A short video

5. The Windlass

6. Superstructures on the deck - the bow hood, the galley and captain's cabin

7. Superstructures on the deck - hatchways

8. Masts

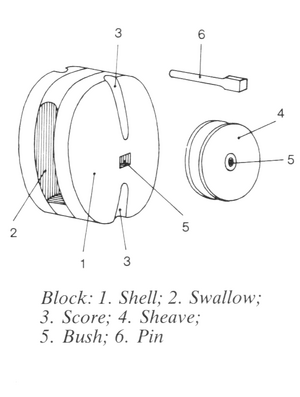

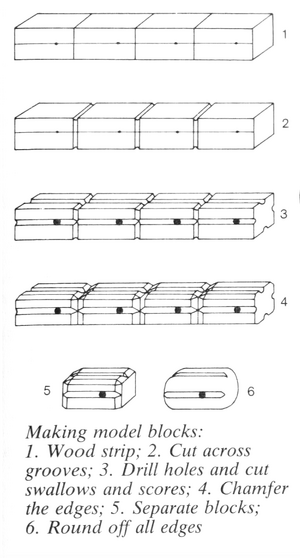

9. Rigging: ropes and blocks

10. Rigging: channels, dead-eyes, gaff and driver boom

11. Sails

12. The anchoring

13. ... to be continued

Last edited: