- Joined

- Jan 9, 2020

- Messages

- 10,378

- Points

- 938

THE FORGOTTEN HISTORY OF THE LITTLE SHIP THAT TOOK ON NOTORIOUS SLAVERS ... AND WON

AMID CANNON-FIRE and gunshot, through smoke thick with gunpowder, Royal Navy brig HMS Black Joke confronted the Spanish slaver El Almirante in a desperate life-or death battle. It was February 1, 1829, and the culmination of a months-long hunt for the infamous slaver and its human cargo of 466 souls.

By: A.E. Rooks

By the time Henry Downes took command of the Black Joke, the ship had only been on the waters under that name for just a year. A former slave ship itself, the Black Joke was captured in 1827 by the British Royal Navy’s West Africa Squadron, its incredible speed repurposed for chasing down and capturing slave traders as they attempted to make their way to the Americas.

For five months, Downes, had been on watch for just one ship—the notorious slaver El Almirante, reputed to be back off the coast of Western Africa and known to have already illegally transported thousands of the enslaved to the Americas in its sordid career. In mid-January 1829, the Black Joke, while patrolling near Lagos, came across what appeared to be several Brazilian slavers embarking Africans. Standing off the coast so as not to spook them, rumor reached Downes that one ship was a fancy, familiar Spanish brig nearly ready to set sail—after the waiting and unproductive cruising, El Almirante had, all unexpected, made its appearance.

On the water, rumors traveled both ways; just as Downes had heard that this was the brig he sought, El Almirante had, in turn, been warned of the appearance of Black Joke. Damaso Forgannes, the recently promoted captain of El Almirante, could not have been less concerned about the prospect of capture. Reputed to have laughed upon hearing the news, Forgannes scoffed publicly at the ludicrous notion of the Black Joke capturing his vessel, continuing to openly purchase enslaved people. The reaction wasn’t entirely unreasonable—El Almirante was an inordinately expensive ship, even for a slaver, purpose-built and equipped with every advance in design its (undoubtedly American) shipwrights could conceive. If making a break for open water was not an option, the slaver crewed upward of 80 men and carried 14 powerful guns.

There was no question that the two-gunned Black Joke, with a crew of 47 plus a temporary supplement of eight men from another Squadron ship, was hugely outpowered in just about every measure. Downes, as undeterred as his opposite number on the slaver, set the Black Joke just out of sight of the harbor, periodically sending boats to check on the progress of the Spanish brig and make sure it continued to load human cargo, since the presence of the enslaved would be the vital evidence against El Almirante that might ultimately condemn it.

Continuing to gather information soon proved worthwhile, especially when a crew member reported back to the Black Joke with the slaver’s destination. Having thus discovered El Almirante’s next port, Downes spent every idle hour calculating the best way to get to the Antilles, moving to a position that hopefully anticipated the correct course. Black Joke was as prepared as it could be. Now, truly, all they could do was wait. Then, on Jan. 31, a fancy Spanish brig appeared with first light. Primed as the crew aboard the Black Joke must have been, they immediately crowded on all sail and, catching a scant breeze, gave chase . . . but the delays weren’t over. In the vital moment, after five months of searching and two weeks of waiting, the wind died. Becalmed, yet undeterred, the crew set to rowing. Nine hours and 30 grueling miles later, they caught the slaver at sunset, who met the Black Joke’s arrival by immediately firing on it.

Everything about catching the Spanish brig had been difficult, and Forgannes had no intention of bucking that trend. Throughout the night, El Almirante repeatedly attempted to close on its would-be captor, firing broadside after broadside. The tender’s bulwarks were not equipped to protect its crew from the slave trader’s heavy armament, so still mostly becalmed, Downes ordered the exhausted crew back to oars. For the rest of the night, far from taking the break they’d richly earned, the Black Joke evaded the slaver by means of paddling rather than tacking sails, always just out of reach of El Almirante’s guns. The move was clever, effective and utterly exhausting. By dawn on Feb. 1, both ships were much as they had been the evening before, still becalmed less than a mile and a half from each other, and with the arrival of the sun, the fighting temporarily ceased. Clearly everyone was prepared for the coming battle, but for the duration of the hot, still morning, both crews could do little else but rest.

Just past noon, the breeze returned. Rather than run, Forgannes moved toward the Black Joke, still certain of victory. Downes, altering his position, wasn’t intimidated. As soon as the Black Joke was within range of grapeshot to the aft of the slaver, Forgannes tried for another broadside. Mortal peril notwithstanding, the crew of the Black Joke had been waiting for this moment for months, and they responded with three cheers and two double-shotted cannons aimed directly at the slave trader’s deck. For 45 minutes the Black Joke held, but when it came to guns, nothing had changed—El Almirante had too many of them. Rather than continue when they were so clearly outmatched, and with the slaver again closing in, Downes switched tactics entirely and gave the order to bring the Black Joke alongside and prepare to board. But suddenly, in what must have been an annoyingly familiar turn of events, the wind died. Again.

This shift in conditions allowed Forgannes to get off a shot that could well have been deadly for everyone aboard the Black Joke had it been better aimed. A light wind 15 minutes later allowed El Almirante, buoyed by the near miss and even more confident in success, to once again take the offensive and move in for another attack. The breeze wasn’t much, but it was enough to give the more maneuverable ship the advantage, and Downes knew exactly which ship that was. In that moment, Downes asked every bit of skill from his crew and everything of Black Joke—and both delivered.

The Black Joke successfully attained El Almirante’s leeward quarter, and from there it gave the slaver all it could handle and then some. For 20 minutes, without pause or respite, the tender raked the quarter and stern of the slaver, and the Black Joke did not miss—seeing the damage subsequently, the Squadron’s Commodore declared that he had “never in his life witnessed a more beautiful specimen of good gunnery.” The repeated attack to just one section of the slave trader created a serious risk of structural damage that, if continued, might well have rendered the ship permanently unseaworthy. Realizing this, El Almirante at last struck its colors and surrendered.

When the Black Joke’s crew finally boarded, they discovered that, regrettably, 11 enslaved people had been killed in the prolonged action. Among the slaver’s crew, 15 were killed, including Forgannes, and every officer but the third mate and 13 wounded. Black Joke had fared better, but had six wounded, two of whom would eventually succumb to their injuries. Both ships’ rigging had taken extensive damage, though El Almirante had the worst of it. The Black Joke had at least one Black, non-Kru seaman, a free African named Joseph Francis, who’d been determined to “strike a personal blow” against the infamous slaver. During the battle, he’d got 12 feet of chain into one of the ship’s guns as it was being loaded; when it was fired, “the starboard main shrouds of the slaver were cut off [. . .] as if by the single blow of an axe.”

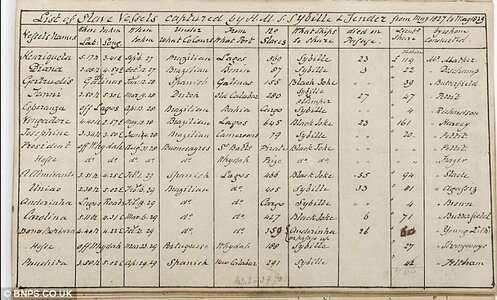

Even with the damage, El Almirante was still a valuable prize, but there was more. One of the Black Joke’s officers, upon searching the slaver, discovered a large cache of gold doubloons; the capture ultimately cost the slaver’s owners roughly “35,000 dollars.” Of arguably more importance—at least to the Squadron—was the additional discovery of cryptic letters in cipher. Less than a week later, Sybille, the Squadron’s flagship, would capture the slaver Uniao, which, during the chase, had been seen tossing papers. When Sybille recovered the letters, they, in conjunction with those found on El Almirante, divulged the nature and location of secret slave trade routes to Havana, then one of the world’s busiest slaving ports. They also warned other slavers that the West Africa Squadron had become an effective force, and only fast, well-armed ships could have a chance of escape. Rumors would continue to spread—the Black Joke was more than just another WAS ship to avoid. It was THE ship to avoid.

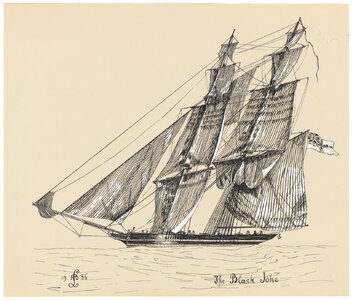

HMS Black Joke takes on Spanish slaver El Almirante

"The Black Joke was Britain's most successful weapon against the slave trade," says A.E. Rooks, author of a compelling new book, The Black Joke. "It was small, fast and relentless, renowned from Africa to South America to England, and feared by slave traders across the seas."

The slavery-hunter's adventures could have been torn from the pages of Patrick O'Brian's Master and Commander novels, which were turned into a Hollywood film starring Russell Crowe. Indeed, they are highly likely to have influenced the novelist in his work. She was embroiled in deadly cannon battles, numerous bloody and hand-to-hand combats, and desperate pursuits across thousands of miles of ocean. Britain had abolished the slave trade in 1807, but halting it was another matter. "Portugal, Spain and Brazil had no intention of giving up slavery, and France had just reinstated it. There was just too much money to be made," explains Rooks. The West Africa Squadron, at the time comprising as few as six vessels, struggled to stem a flood of slavers. By 1830, slavers annually transported some 80,000 captives from Africa in a trade that ultimately saw 12.5 million people shipped in chains.

The Black Joke was smaller than most vessels it hunted, only 90ft long by 26ft broad, usually with fewer than 50 crew, but had been built in America for speed and maneuverability. "The small brig would come to symbolise new methods and ideas for fighting slavery, heralding the possibility a moral and ethical disgrace global in scope and centuries in the making could actually be fought and quickly dismantled, piece by piece," says Rooks. Yet the Black Joke began life ignominiously as the Brazilian slave ship Henriqueta in 1825, and in a series of voyages transported some 3,500 captives from Africa across the Atlantic in hellish conditions. On its journey of September 1827, 569 souls were loaded aboard in Lagos, bound for Brazil.

Shackled and chained, squeezed into cramped quarters too confined to sit up, sick with dysentery, whipped and flogged, open to rape and abuse by cruel sailors, about one fifth were expected to die before ever reaching their destination. "There was unimaginable human suffering on the slave ships," says the author. "Enslaved captives chained below deck could suffocate or die from heat and thirst. They lay in their own excrement, many on top of the rotting bodies of other dead slaves." Captured by the HMS Sybille, the Henriqueta's surviving captives were freed, and the brig sold at auction, becoming a slave ship-hunter for the British Royal Navy.

She was renamed the Black Joke: a wry commentary on the slave trade, and also a lewd reference to a woman's private parts in a popular song of the era. The Royal Navy's West Africa Squadron routinely spent months sailing open oceans to find a slave ship, but it took the Black Joke only a week before she spied her first prey: a Spanish slaver called the Gertrudis, carrying 155 slaves. The Black Joke gave chase for 24 hours, as the Gertrudis threw overboard everything to lighten its load, including its cannons. Finally outrun, it surrendered without firing a single shot.

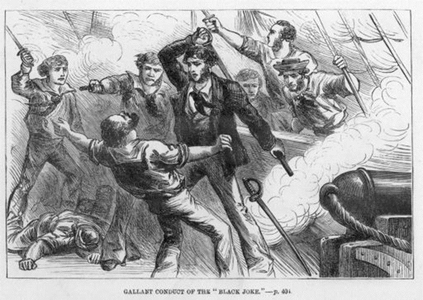

"The word quickly spread that the Black Joke was the ship to avoid," says Rooks. "Slave ship captains would wait months in port rather than risk capture by the Black Joke, which developed a fearsome reputation." Some gave up without a fight; others battled fiercely, but few more so than the Marinerito, carrying 496 slaves in April 1831. When winds dropped during the chase, the Black Joke rowed for an hour through heavy gunfire to board the Spanish slaver, its 18 guns blazing. "It was one of the most violent hand-to-hand combats the Black Joke ever saw," explains Rooks.

"As the two ships came alongside the officers of the Black Joke leaped aboard the Marinerito with swords and guns, but the Black Joke ricocheted away, stranding the handful of British facing 77 Spanish seamen. A 15-year-old midshipman was the only officer left on the Black Joke, but he got the two boats lashed together and when the smoke cleared the Spanish surrendered, wounded with 13 dead and 15 wounded. Though her captain and mate were badly wounded, the Black Joke lost only one man. But it was the enslaved who suffered most. Trapped below decks for the 24-hour pursuit without water, 26 died of heat, suffocation and thirst, and 60 more perished within days. HMS Black Joke's crew were so horrified that they marooned the surviving slavers on a remote island. Yet the Black Joke witnessed even worse horrors when pursuing Spanish slaver the Rapido, which threw its 450 shackled slaves overboard to drown or be eaten by sharks, rather than let the vessel be confiscated if caught with slaves aboard.

Though battling slavery, not all the Black Joke's crew supported abolition, and many were likely to be convinced of white supremacy, Rooks believes. "Many in the Admiralty thought it was a losing battle trying to stop the slave trade, and with British paternalism and colonialism there was a belief in African inferiority." Frustratingly, many of the captured slave ships were sold at auction to other slavers and returned to grim service, while some cynical British naval officers even retired from the service to become slavers themselves.

Barely seaworthy after her many battles, the Black Joke still sailed circles around the British Navy's two newest vessels in a sea trial that humiliated the West Africa Squadron's new commodore in 1832. Piqued, he ordered the Black Joke - her timbers rotting and reaching the end of their life - to be unceremoniously burned in Sierra Leone. "Freed slaves petitioned to save the vessel, offering to buy her, but the commodore refused, and the Black Joke was reduced to ashes," says Rooks. "Slavers from Africa to Brazil celebrated her demise. In the fight against slavery the Black Joke was a valiant warrior. She deserved a better end."

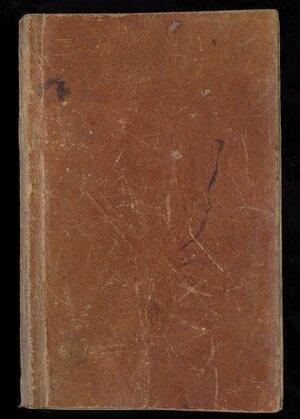

All that remains of the Black Joke today are her log book, an elaborate snuff box carved from her beams, and an envelope hidden away in the National Archive that once held wood from her timbers ... long since turned to dust.

Black Joke's Log Book and Snuff Box

List of Captured ships recorded in the log book.

The Black Joke: The True Story of One British Ship's Battle Against the Slave Trade by A.E. Rooks

Product details

- Publisher : Scribner; First Edition (January 18, 2022)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 400 pages

- ISBN-10 : 1982128267

- ISBN-13 : 978-1982128265