.

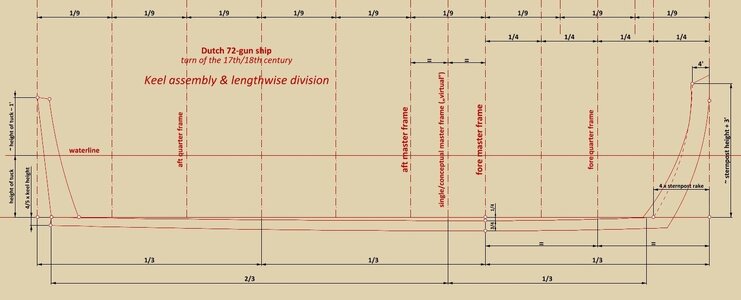

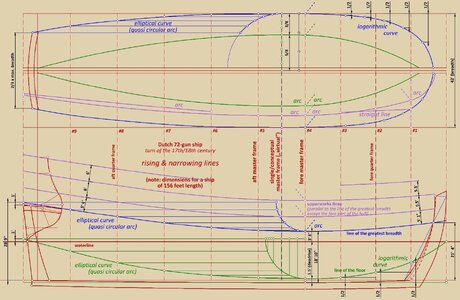

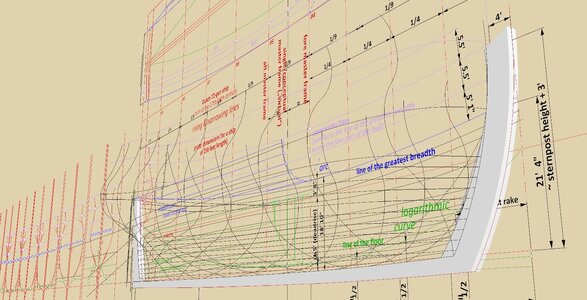

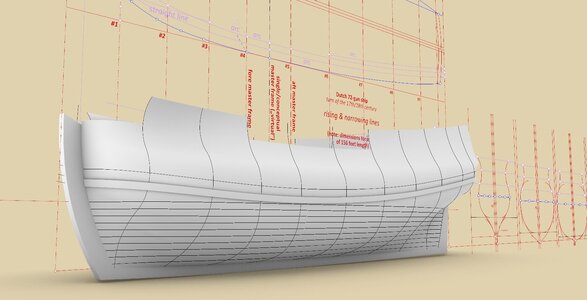

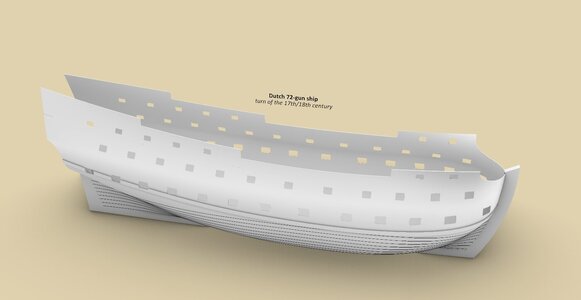

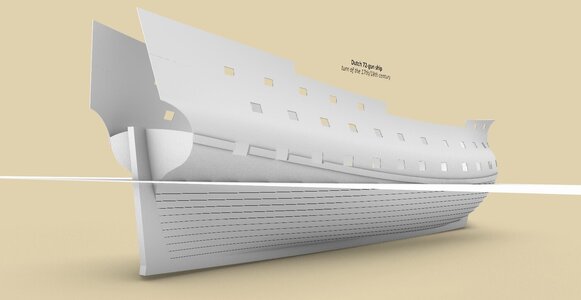

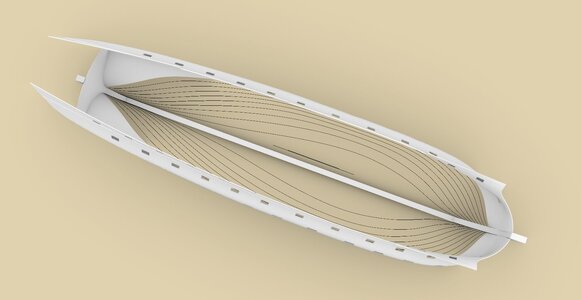

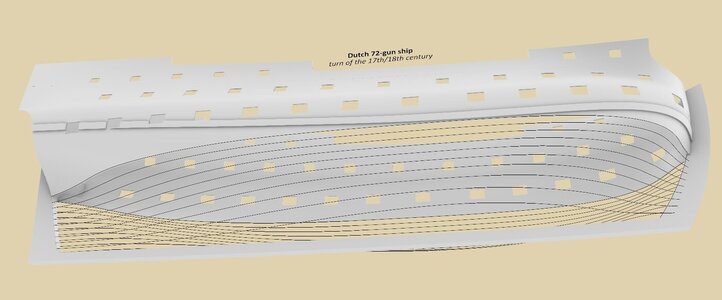

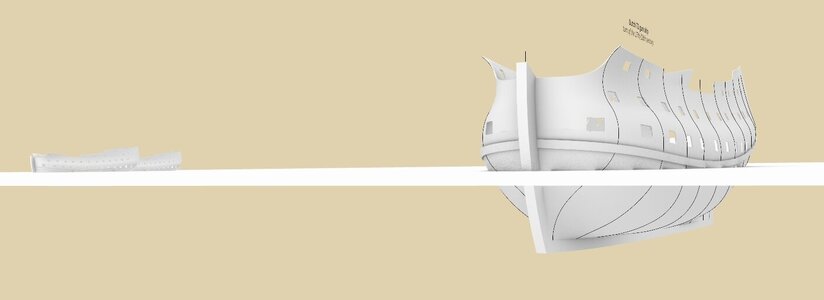

It should be clarified at once that this plan, tentatively dated by me to the end of the 17th century, is one of the last of the era before the widespread adoption of design diagonals, which in the Netherlands occurred in the third decade of the 18th century at the latest (see as to this Ab Hoving & Alan Lemmers, In Tekening Gebracht. De achttiende-eeuwse scheepsbouwers en hun ontwerpmethoden, 2001). In historical terms, this is the period of the Third Anglo-Dutch War (1672–1674), the War of the League of Augsburg (1688–1697) and the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714).As it seems, this very plan was not previously widely known and was kindly provided to me for examination, in terms of the design method used, by Ab Hoving. This is an exceptionally fortunate circumstance for several reasons, and I am most pleased that it demonstrates classical prediagonal design methods in their latest, most advanced form and for the most demanding projects, that is of a dedicated warships.

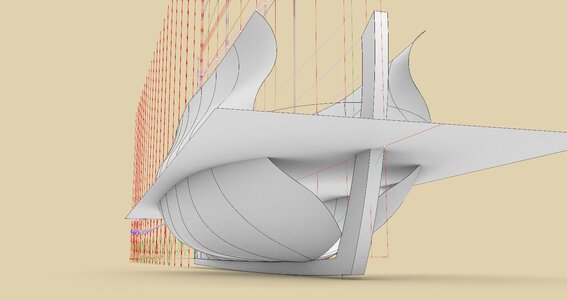

It is apparent at first glance that conceptually this is a more sophisticated design compared to the civilian designs presented so far (Samuel 1650, Witsen’s pinas 1671, Rålamb's boyer & fluit 1691), while it is more similar in this sense to the Dutch capital ship ca. 1665 (Hohenzollern model), the French (Atlantic) heavy frigate design by Chaillé 1686 and the designs of 1679 by Hubacs of Dutch origin, boasting dozens of designed and built ships to their credit.

* * *

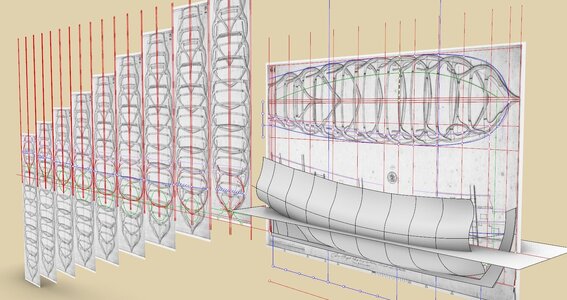

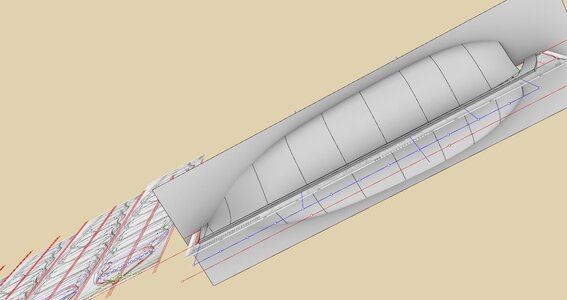

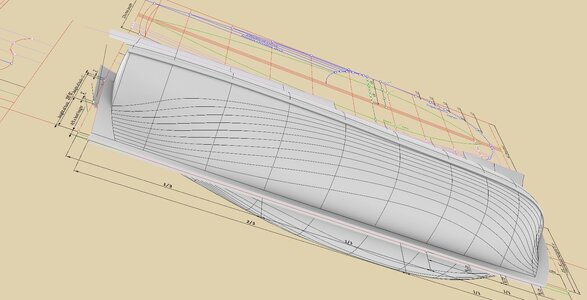

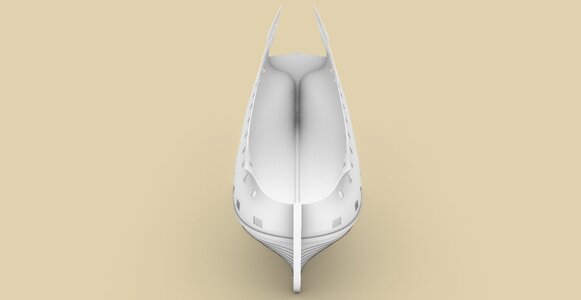

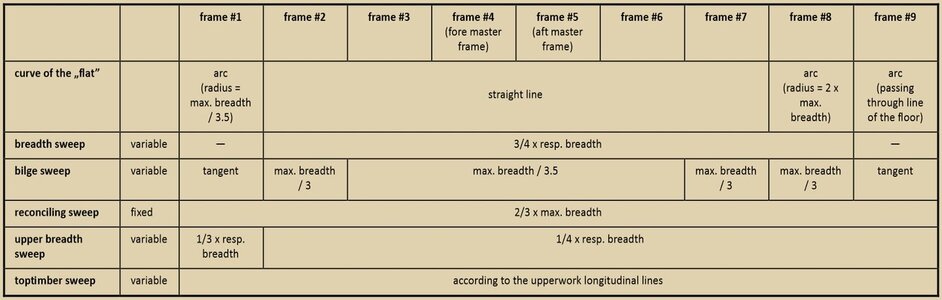

The primary aim of the project will not even be to search for all the (main) proportions of the design parameters, as many of them were quite arbitrary (as they still are today), but rather to search for more universal procedures applied for shaping the body of the hull, quite independent of these proportions.

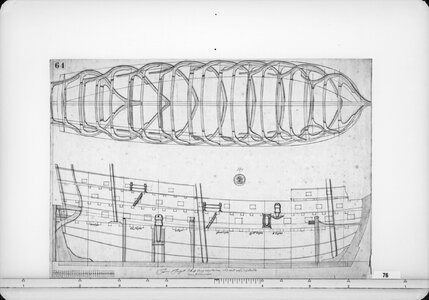

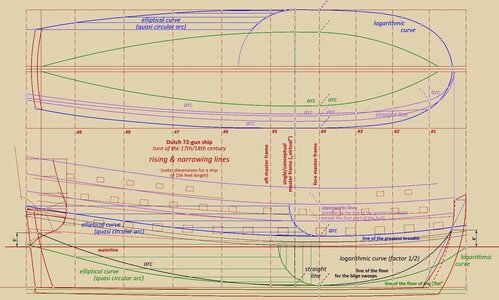

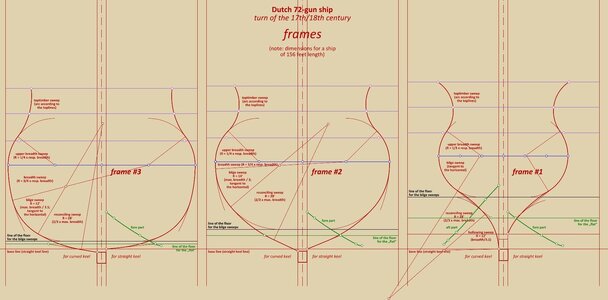

The plan (Archives of the Nederlandsche Marine):

.