Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

20 November 1845 – Anglo-French blockade of the Río de la Plata: Battle of Vuelta de Obligado.

The naval Battle of Vuelta de Obligado took place on the waters of the Paraná River on 20 November 1845, between the Argentine Confederation, under the leadership of Juan Manuel de Rosas, and a combined Anglo-French fleet. The action was part of the larger Anglo-French blockade of the Río de la Plata. Although the attacking forces broke through the Argentine naval defenses and overran the land defenses, the battle proved that foreign ships could not safely navigate Argentine internal waters against its government's wishes. The battle also changed political feeling in South America, increasing support for Rosas and his government.

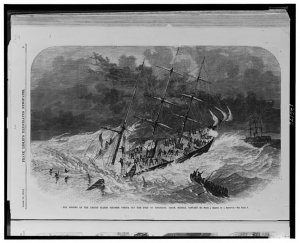

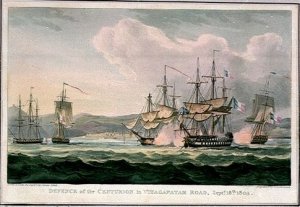

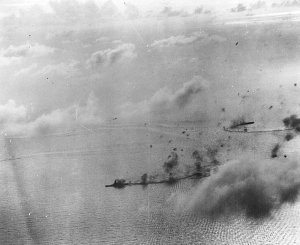

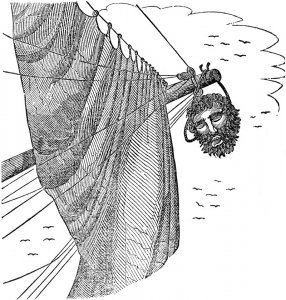

The Anglo-French armada forces its way through the Vuelta de Obligado

Background

During the 1830s and 1840s, the British and French governments were at odds with Rosas' leadership of the Argentine Confederation. Rosas' economic policies of requiring trade to pass through the Buenos Aires custom house – which was his method of imposing his will on the Littoral provinces – combined with his attempts to incorporate Paraguay and Uruguay to the Confederation, were in conflict with French and British economic interests in the region. During his government, Rosas had to face numerous problems with these foreign powers, which in some cases reached levels of open confrontation. These incidents included two naval blockades, the French blockade in 1838, and the Anglo-French of 1845.

With the development of steam-powered sailing (which mainly took place in Great Britain, France and the United States) in the third decade of the 19th century, large merchant and military ships became capable of sailing up rivers at a good speed and with a heavy load. This new technology allowed the British and French governments to avoid the custom house in Buenos Aires by sailing directly through the La Plata estuary and engaging in commerce directly with inland cities in Entre Ríos, Corientes, Uruguay and Paraguay. This avoided Buenos Aires' taxation, guaranteed special rights for the Europeans and allowed them to export their products cheaply.

Rosas' government tried to stop this practice by declaring the Argentine rivers closed to foreign countries, barring access to Paraguay and other ports in the process. The British and French governments did not acknowledge this declaration and decided to defy Rosas by sailing upstream with a joint fleet, setting the stage for the battle.

Battle

Order of battle

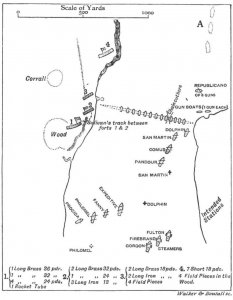

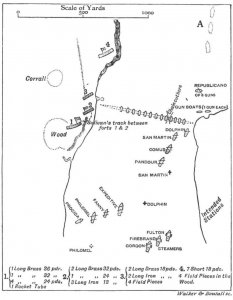

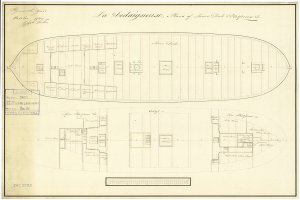

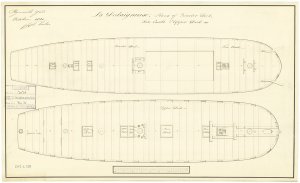

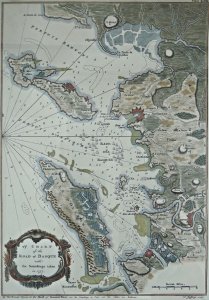

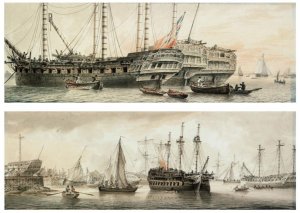

British and French boats assaulting the chain line at Obligado

The Anglo-French squadron that was sailing through the Paraná river in the first days of November was composed of eleven warships.

The main Argentine redoubt was located on a cliff rising between 30 and 180 m over the banks at Vuelta de Obligado, where the river is 700 metres wide and a turn makes navigation difficult.

The Argentine general Lucio N. Mansilla set up three thick metal chains suspended from 24 boats completely across the river, to prevent the advance of the European fleet. This operation was under the charge of an Italian immigrant named Filipo Aliberti. Only three of these boats were naval vessels; the rest were requisitioned barges whose owners received a compensation in case of loss. Aliberti was the master of one of the boats, the Jacoba, sunk in the battle. At least 20 boats and barges were lost in the chain barrage at Obligado.

Chain links and ammunition used by the Argentine forces during the battle

On the right shore of the river the Argentines mounted four batteries with 30 cannons, many of them bronze 8, 10, 12 and 20-pounders. These were served by a division of 160 gaucho soldiers. There were also 2,000 men in trenches under the command of ColonelRamón Rodríguez (es), together with the brigantine Republicano (es) and two small gunboats, Restaurador and Lagos,[13][8] with the mission of guarding the chains across the river. Some sources increase the Argentine naval power to a third gunboat, the unarmed brigantine Vigilante, whose artillery had been dismounted and transferred to one of the batteries, eight armed launches and at least five armed barges.

Main action

The combat began at dawn, with intense cannon fire and rocket discharges over the Argentine batteries, which had less accurate and slower loading cannons. From the beginning the Argentines suffered many casualties — 150 dead, 90 wounded. Furthermore, the barges that held the chains were burnt down, and the Republicano was lost, blown up by its own commander when he was unable to defend it any longer. A number of armed launches were also sunk in battle. The gunboats Restaurador and Lagos disengaged successfully and withdrew up river, towards Tonelero pass. The third gunboat and the armed barges also survived the action, but the dismantled brigantine Vigilante was scuttled by her crew and the remaining launches were destroyed by the combined fleet on 28 November.

Shortly after, the French steamer Fulton sailed through a gap open in the chain's barrier. Disembarked troops overcame the last defenders of the bluff, and 21 cannons fell into hands of the allied forces.

The Europeans had won free passage at the cost of 28 dead and 95 wounded. However, the ships suffered severe damage, stranding them at Obligado for 40 days to make emergency repairs.

Secondary action

Meanwhile, 40 km to the north, a small Argentine naval force composed of the sloop Chacabuco, the gunboats Carmen, Arroyo Grande, Apremio and Buena Vista kept watch over a secondary branch of the Paraná whose control gives full access to the ports of Entre Ríos. Like at Obligado, a double chain held by seven barges was also deployed across the river. When news of the battle's outcome reached the squadron, the Chacabuco was scuttled and the remainder of the flotilla took shelter in the port of Victoria.

Upstream

Only 50 out of 92 merchantmen awaiting at Ibicuy Islands continued their upriver trip. The rest gave up and returned to Montevideo. The British and French ships that were able to sail past up river were again attacked on their way back at Paso del Tonelero and at Angostura del Quebracho on 4 June 1846. The combined fleet suffered the loss of six merchant ships during the later engagement.

Aftermath

The Anglo-French victory did not achieve their economic objectives. It proved to be practically impossible to sail Argentine rivers without the authorisation of Argentine authorities.

The battle had a great impact on the continent. Chile and Brazil changed their stance (until then they were against Rosas), and supported the Confederation. Even some Unitarian leaders, traditional enemies of the Argentine caudillo, were moved by the events, with General Martiniano Chilavert offering to join the Confederacy army.

France and the United Kingdom eventually lifted the blockade and dropped their attempts to bypass Buenos Aires' policies. They acknowledged the Argentine government's legal right over the Paraná and other internal rivers, and its authority to determine who had access to it, in exchange for the withdrawal of Rosas's army from Uruguay.

The Battle of Obligado is remembered in Argentina on 20 November, which was declared a "Day of National Sovereignty" in 1974, and became a national holiday in 2010. The French Paris Métro had a station named after this battle until 1947, when it was renamed Argentine, as a good-will gesture after the visit of Eva Perón to France.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anglo-French_blockade_of_the_Río_de_la_Plata

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Vuelta_de_Obligado

20 November 1845 – Anglo-French blockade of the Río de la Plata: Battle of Vuelta de Obligado.

The naval Battle of Vuelta de Obligado took place on the waters of the Paraná River on 20 November 1845, between the Argentine Confederation, under the leadership of Juan Manuel de Rosas, and a combined Anglo-French fleet. The action was part of the larger Anglo-French blockade of the Río de la Plata. Although the attacking forces broke through the Argentine naval defenses and overran the land defenses, the battle proved that foreign ships could not safely navigate Argentine internal waters against its government's wishes. The battle also changed political feeling in South America, increasing support for Rosas and his government.

The Anglo-French armada forces its way through the Vuelta de Obligado

Background

During the 1830s and 1840s, the British and French governments were at odds with Rosas' leadership of the Argentine Confederation. Rosas' economic policies of requiring trade to pass through the Buenos Aires custom house – which was his method of imposing his will on the Littoral provinces – combined with his attempts to incorporate Paraguay and Uruguay to the Confederation, were in conflict with French and British economic interests in the region. During his government, Rosas had to face numerous problems with these foreign powers, which in some cases reached levels of open confrontation. These incidents included two naval blockades, the French blockade in 1838, and the Anglo-French of 1845.

With the development of steam-powered sailing (which mainly took place in Great Britain, France and the United States) in the third decade of the 19th century, large merchant and military ships became capable of sailing up rivers at a good speed and with a heavy load. This new technology allowed the British and French governments to avoid the custom house in Buenos Aires by sailing directly through the La Plata estuary and engaging in commerce directly with inland cities in Entre Ríos, Corientes, Uruguay and Paraguay. This avoided Buenos Aires' taxation, guaranteed special rights for the Europeans and allowed them to export their products cheaply.

Rosas' government tried to stop this practice by declaring the Argentine rivers closed to foreign countries, barring access to Paraguay and other ports in the process. The British and French governments did not acknowledge this declaration and decided to defy Rosas by sailing upstream with a joint fleet, setting the stage for the battle.

Battle

Order of battle

British and French boats assaulting the chain line at Obligado

The Anglo-French squadron that was sailing through the Paraná river in the first days of November was composed of eleven warships.

- British

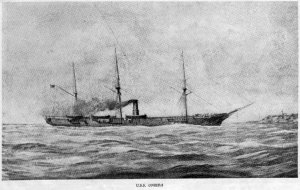

- Gorgon, paddle (6 guns, Capt. Charles Hotham)

- Firebrand, paddle (6 guns, Capt. James Hope)

- Philomel (8 guns, Commander Bartholomew James Sulivan)

- Comus (18 guns, Commander Edward Augustus Inglefield (acting))

- Dolphin (3 guns, Lieut. Reginald Thomas John Levinge)

- Fanny, schooner (1 gun, Lieut. Astley Cooper Key)

- French

- San Martin (8 guns, Capt. François Thomas Tréhouart)

- Fulton, paddle (2 guns, Lieut. Louis Mazères (fr))

- Expéditive (16 guns, Lieut. Miniac)

- Pandour (10 guns, Lieut. Duparc)

- Procida (4 guns, Lieut. de la Rivière)

The main Argentine redoubt was located on a cliff rising between 30 and 180 m over the banks at Vuelta de Obligado, where the river is 700 metres wide and a turn makes navigation difficult.

The Argentine general Lucio N. Mansilla set up three thick metal chains suspended from 24 boats completely across the river, to prevent the advance of the European fleet. This operation was under the charge of an Italian immigrant named Filipo Aliberti. Only three of these boats were naval vessels; the rest were requisitioned barges whose owners received a compensation in case of loss. Aliberti was the master of one of the boats, the Jacoba, sunk in the battle. At least 20 boats and barges were lost in the chain barrage at Obligado.

Chain links and ammunition used by the Argentine forces during the battle

On the right shore of the river the Argentines mounted four batteries with 30 cannons, many of them bronze 8, 10, 12 and 20-pounders. These were served by a division of 160 gaucho soldiers. There were also 2,000 men in trenches under the command of ColonelRamón Rodríguez (es), together with the brigantine Republicano (es) and two small gunboats, Restaurador and Lagos,[13][8] with the mission of guarding the chains across the river. Some sources increase the Argentine naval power to a third gunboat, the unarmed brigantine Vigilante, whose artillery had been dismounted and transferred to one of the batteries, eight armed launches and at least five armed barges.

Main action

The combat began at dawn, with intense cannon fire and rocket discharges over the Argentine batteries, which had less accurate and slower loading cannons. From the beginning the Argentines suffered many casualties — 150 dead, 90 wounded. Furthermore, the barges that held the chains were burnt down, and the Republicano was lost, blown up by its own commander when he was unable to defend it any longer. A number of armed launches were also sunk in battle. The gunboats Restaurador and Lagos disengaged successfully and withdrew up river, towards Tonelero pass. The third gunboat and the armed barges also survived the action, but the dismantled brigantine Vigilante was scuttled by her crew and the remaining launches were destroyed by the combined fleet on 28 November.

Shortly after, the French steamer Fulton sailed through a gap open in the chain's barrier. Disembarked troops overcame the last defenders of the bluff, and 21 cannons fell into hands of the allied forces.

The Europeans had won free passage at the cost of 28 dead and 95 wounded. However, the ships suffered severe damage, stranding them at Obligado for 40 days to make emergency repairs.

Secondary action

Meanwhile, 40 km to the north, a small Argentine naval force composed of the sloop Chacabuco, the gunboats Carmen, Arroyo Grande, Apremio and Buena Vista kept watch over a secondary branch of the Paraná whose control gives full access to the ports of Entre Ríos. Like at Obligado, a double chain held by seven barges was also deployed across the river. When news of the battle's outcome reached the squadron, the Chacabuco was scuttled and the remainder of the flotilla took shelter in the port of Victoria.

Upstream

Only 50 out of 92 merchantmen awaiting at Ibicuy Islands continued their upriver trip. The rest gave up and returned to Montevideo. The British and French ships that were able to sail past up river were again attacked on their way back at Paso del Tonelero and at Angostura del Quebracho on 4 June 1846. The combined fleet suffered the loss of six merchant ships during the later engagement.

Aftermath

The Anglo-French victory did not achieve their economic objectives. It proved to be practically impossible to sail Argentine rivers without the authorisation of Argentine authorities.

The battle had a great impact on the continent. Chile and Brazil changed their stance (until then they were against Rosas), and supported the Confederation. Even some Unitarian leaders, traditional enemies of the Argentine caudillo, were moved by the events, with General Martiniano Chilavert offering to join the Confederacy army.

France and the United Kingdom eventually lifted the blockade and dropped their attempts to bypass Buenos Aires' policies. They acknowledged the Argentine government's legal right over the Paraná and other internal rivers, and its authority to determine who had access to it, in exchange for the withdrawal of Rosas's army from Uruguay.

The Battle of Obligado is remembered in Argentina on 20 November, which was declared a "Day of National Sovereignty" in 1974, and became a national holiday in 2010. The French Paris Métro had a station named after this battle until 1947, when it was renamed Argentine, as a good-will gesture after the visit of Eva Perón to France.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anglo-French_blockade_of_the_Río_de_la_Plata

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Vuelta_de_Obligado

age

age

, Virginia.

, Virginia.