Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

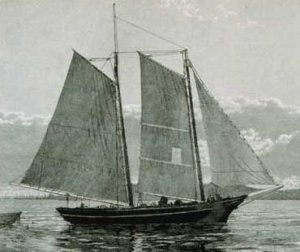

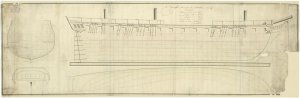

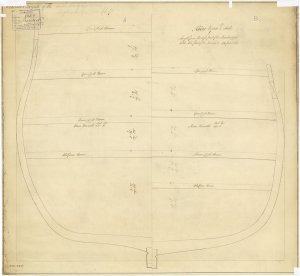

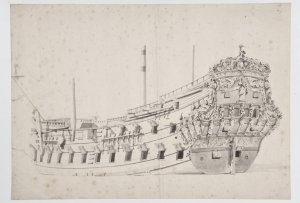

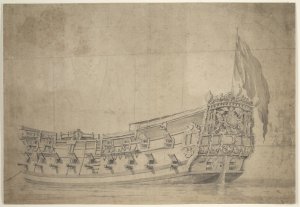

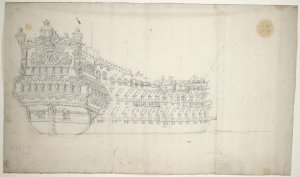

13 December 1693 - Death of Willem van de Velde the Elder

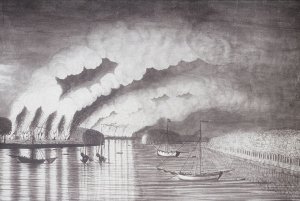

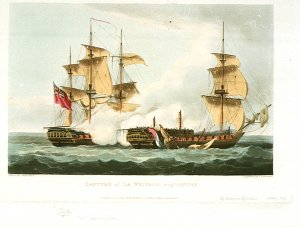

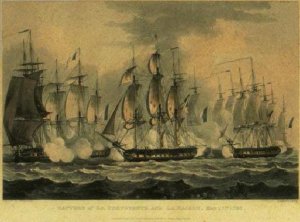

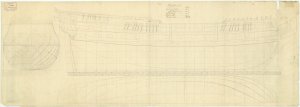

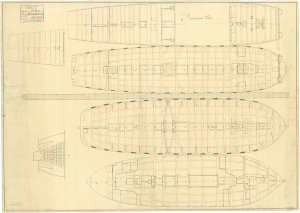

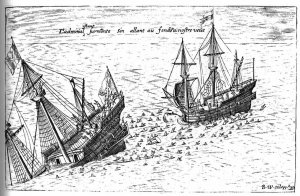

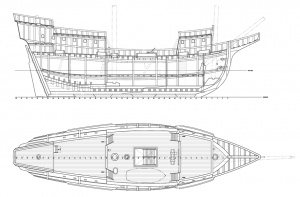

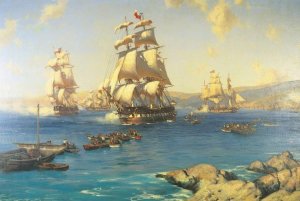

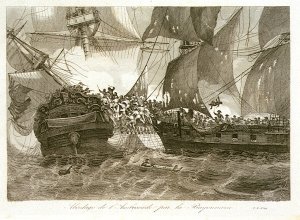

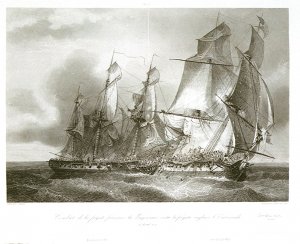

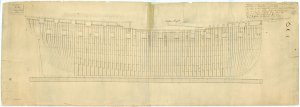

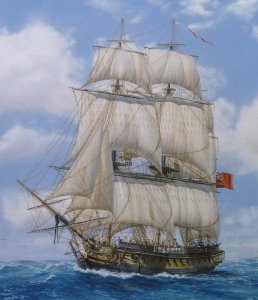

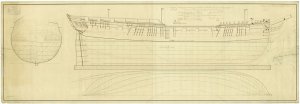

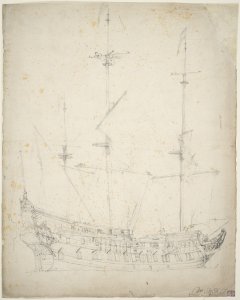

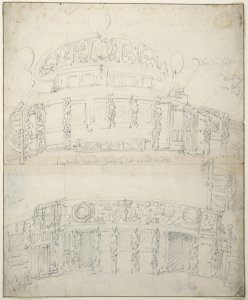

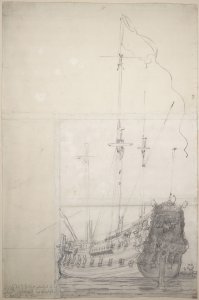

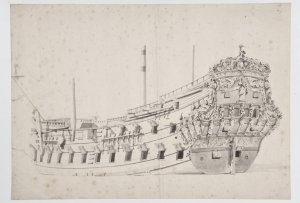

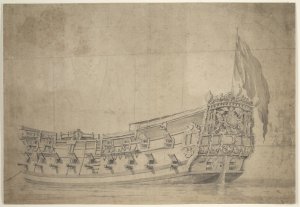

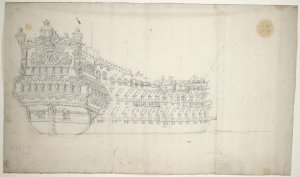

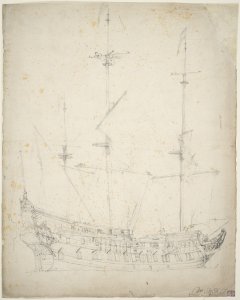

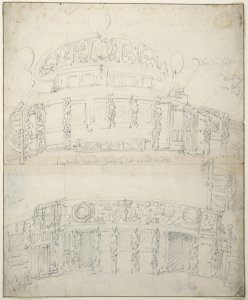

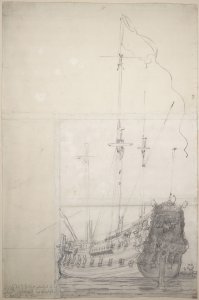

Because of painters like him, we know now, how these ships were looking like

Willem van de Velde the Elder (c. 1611 – 13 December 1693) was a Dutch Golden Age seascape painter.

Biographical Outline

Willem van de Velde, known as the Elder, a marine draughtsman and painter, was born in Leiden, the son of a Flemish skipper, Willem Willemsz. van de Velde, and is commonly said to have been bred to the sea. In 1706 Bainbrigg Buckeridge noted that he “understood navigation very well”. He married Judith Adriaensdochter van Leeuwen in Leiden, the Netherlands, in 1631.

His three known legitimate children were named Magdalena, born 1632; Willem, known as the Younger, also a marine painter, born 1633; and Adriaen, a landscape painter, born 1636.

His marriage was stormy, at least in its later years. David Cordingly relates that Willem the Elder fathered two children out of wedlock in 1653, one “by his maidservant, and the other by her friend. Nine years later the Elder and his wife went through a legal separation, ‘on account of legal disputes and the most violent quarrels’. The immediate cause of the dispute was his affair with a married woman.” Michael S. Robinson noted that “on 17/27 July 1662, he and his wife agreed to part. A condition of the separation was that the Elder could recover from his son Adriaen ‘two royal gifts’, presumably gifts from Charles II for work done in England.” Cordingly’s account further relates that the dispute was still continuing after another ten years, since “in the autumn of 1672 Judith complained to the woman’s husband.” Robinson adds that by 1674 the couple “must have been reconciled”, for at a chance meeting with Pieter Blaeu in Amsterdam in July the Elder explained that he was only visiting for a few days “in order to fetch his wife”. His son, Adriaen, had died in Amsterdam in 1672, and Willem the Elder was also fetching his grandson, similarly named Adriaen, who was then aged two.

After his move to England, the exact date of which is uncertain, but reportedly at the end of 1672 or beginning of 1673, he is said to have lived with his family in East Lane, Greenwich, and to have used the Queen’s House, now part of the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, as a studio. Following the accession of William III and Mary II as King and Queen of England, it appears that this facility was no longer provided, and by 1691 he was living in Sackville Street, now close to Piccadilly Circus. He died in London, and was buried in St James’s Church, at the south end of the street.

Professional career

He was the official artist of the Dutch fleet for a period, being present at the Four Days Battle, 1–4 June 1666, and the St James's Day Battle, 25 July 1666, to make sketches. In his work on the biographies of artists, Arnold Houbraken quotes Gerard Brandt's biography of Admiral Michiel de Ruyter,[1]relating the anecdote where Willem van de Velde asked Admiral de Ruyter permission to have a galley row him around for a good view of the proceedings on the evening of the Four Days battle in 1666. He wasn't the only artist to paint the scenes of this battle, his son, Ludolf Bakhuysen and Pieter Cornelisz van Soest also made paintings of it. This act later was the reason that van Velde gained his marine commission in London. The date, 1672, commonly given for his entry into the service of Charles II of England, was at a time when the Dutch Republic was at war with England (Third Anglo-Dutch War).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Willem_van_de_Velde_the_Elder

http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collec...ity=subject-90582;browseBy=collection;start=0

13 December 1693 - Death of Willem van de Velde the Elder

Because of painters like him, we know now, how these ships were looking like

Willem van de Velde the Elder (c. 1611 – 13 December 1693) was a Dutch Golden Age seascape painter.

Biographical Outline

Willem van de Velde, known as the Elder, a marine draughtsman and painter, was born in Leiden, the son of a Flemish skipper, Willem Willemsz. van de Velde, and is commonly said to have been bred to the sea. In 1706 Bainbrigg Buckeridge noted that he “understood navigation very well”. He married Judith Adriaensdochter van Leeuwen in Leiden, the Netherlands, in 1631.

His three known legitimate children were named Magdalena, born 1632; Willem, known as the Younger, also a marine painter, born 1633; and Adriaen, a landscape painter, born 1636.

His marriage was stormy, at least in its later years. David Cordingly relates that Willem the Elder fathered two children out of wedlock in 1653, one “by his maidservant, and the other by her friend. Nine years later the Elder and his wife went through a legal separation, ‘on account of legal disputes and the most violent quarrels’. The immediate cause of the dispute was his affair with a married woman.” Michael S. Robinson noted that “on 17/27 July 1662, he and his wife agreed to part. A condition of the separation was that the Elder could recover from his son Adriaen ‘two royal gifts’, presumably gifts from Charles II for work done in England.” Cordingly’s account further relates that the dispute was still continuing after another ten years, since “in the autumn of 1672 Judith complained to the woman’s husband.” Robinson adds that by 1674 the couple “must have been reconciled”, for at a chance meeting with Pieter Blaeu in Amsterdam in July the Elder explained that he was only visiting for a few days “in order to fetch his wife”. His son, Adriaen, had died in Amsterdam in 1672, and Willem the Elder was also fetching his grandson, similarly named Adriaen, who was then aged two.

After his move to England, the exact date of which is uncertain, but reportedly at the end of 1672 or beginning of 1673, he is said to have lived with his family in East Lane, Greenwich, and to have used the Queen’s House, now part of the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, as a studio. Following the accession of William III and Mary II as King and Queen of England, it appears that this facility was no longer provided, and by 1691 he was living in Sackville Street, now close to Piccadilly Circus. He died in London, and was buried in St James’s Church, at the south end of the street.

Professional career

He was the official artist of the Dutch fleet for a period, being present at the Four Days Battle, 1–4 June 1666, and the St James's Day Battle, 25 July 1666, to make sketches. In his work on the biographies of artists, Arnold Houbraken quotes Gerard Brandt's biography of Admiral Michiel de Ruyter,[1]relating the anecdote where Willem van de Velde asked Admiral de Ruyter permission to have a galley row him around for a good view of the proceedings on the evening of the Four Days battle in 1666. He wasn't the only artist to paint the scenes of this battle, his son, Ludolf Bakhuysen and Pieter Cornelisz van Soest also made paintings of it. This act later was the reason that van Velde gained his marine commission in London. The date, 1672, commonly given for his entry into the service of Charles II of England, was at a time when the Dutch Republic was at war with England (Third Anglo-Dutch War).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Willem_van_de_Velde_the_Elder

http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collec...ity=subject-90582;browseBy=collection;start=0