Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

12 November 1965 - SS Yarmouth Castle burning

SS Yarmouth Castle was an American steamship whose loss in a disastrous fire in 1965 prompted new laws regarding safety at sea.

Yarmouth Castle sailing under her original name, Evangeline

Early history

She was built in 1927 by the William Cramp & Sons Ship and Engine Building Company in Philadelphia. She was christened Evangeline and renamed Yarmouth Castle in 1964.[1] The ship was 365 feet long and measured 5,002 gross tons. Her sister ship, Yarmouth, was launched the same year. Her sister was named Yarmouth till 1954, then renamed several times, Queen of Nassau 1954, Yarmouth Castle 1957, San Andred 1966, Elizabeth A 1967, she was scrapped in 1977.

Evangeline operated the Boston – Yarmouth, Nova Scotia service for the Eastern Steamship Lines until World War II, when she was sent to the Pacific to serve as a troop ship. The ship ferried combat troops from San Francisco to the island battlefronts and also served as a hospital ship. After being refitted and refinished at the Bethlehem Steel Corporation's shipyards at a cost of US$1.5 million, she returned to passenger service in May 1947.

She operated on the New York City – Bahamas run for less than a year, and was then laid up from 1948 to 1953, save for a two-month period in 1950. The ship was sold to a Liberian company called the Volusia Steamship Company in 1954. She was given an overnight run from Boston to Nova Scotia, and resumed service to the Caribbean in 1955.

The ship was sold in 1963 to the Chadade Steamship Company, and her name was changed to Yarmouth Castle that year. She offered service from New York City to the Bahamas for Caribbean Cruise Lines, which went bankrupt that same year. By the end of 1964, Yarmouth Castle was operated by Yarmouth Cruise Lines. The ship ran pleasure cruises on the 186-mile stretch between Miami and Nassau. She was under Panamanian registry.

Fire

Yarmouth Castle departed Miami for Nassau on November 12, 1965, with 376 passengers and 176 crewmen aboard, a total of 552 people. The ship was due to arrive in Nassau the next day. The captain on the voyage was 35-year-old Byron Voutsinas.

Shortly before 1:00 a.m. on November 13, a mattress stored too close to a lighting circuit in a storage room, Room 610, caught fire. The room was filled with mattresses and paint cans, which fed the flames.

At around 1:00, a badly burned passenger emerged from a stairway and collapsed on the deck. Crewmen who rushed to the man's aid found the stairwell filled with smoke and flames. Captain Voutsinas was immediately notified of the fire by the watch officer. The captain ordered the second mate to sound the alarm on the ship's whistle, but the bridge went up in flames before the alarm could be sounded. The ship's radio operator, who had been off duty, found the radio shack to be completely ablaze by the time he reached it. By this point, Yarmouth Castle was 120 miles east of Miami and 60 miles northwest of Nassau.

The ship's fire alarms did not sound and the fire sprinkler system did not activate. Passengers were awakened by screaming and running in the corridors as people frantically tried to find lifejackets.

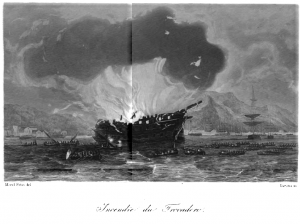

Photograph of the fire taken from the boat deck of Bahama Star

The fire swept through the ship's superstructure at great speed, driven by the ship’s natural ventilation system. The flames rose vertically through the stairwells, fueled by the wood paneling, wooden decks and layers of fresh paint on the walls. Many passengers had to break windows and squeeze through portholes to exit their burning cabins. The whole front half of the ship was quickly engulfed, causing passengers and crew to flee to the stern of the ship. Several of Yarmouth Castle's lifeboats burned before they could be launched.

More problems ensued. The ship's fire hoses had inadequate water pressure to fight the fire. One of the hoses had even been cut. Additionally, the swimming pool was connected to the fire pump system by way of an open valve which allowed the pool to fill and thereby reduced water pressure. Crewmen also had difficulty launching the lifeboats. The ropes used to lower the boats had been covered in thick coats of paint, causing them to jam in the winches. Even the boats that were successfully lowered had no rowlocks, and had to be paddled like canoes. In the end, only six of the 13 lifeboats were launched.

There were tales of both courage and cowardice among the crew. Many fled the ship without helping the passengers. Others pulled passengers from the windows of their cabins and directed them to rope ladderson the side of the ship. Some crew members had to physically throw weak and panic-stricken people off the side of the ship, away from the spreading flames. Several sailors even gave away their lifejackets.

The Finnish freighter Finnpulp was just eight miles ahead of Yarmouth Castle, also headed east. At 1:30 a.m., the ship's mate noticed that Yarmouth Castle had slowed significantly on the radar screen. Looking astern, he saw the glowing flames and notified the captain, John Lehto, who had been asleep. Lehto immediately ordered Finnpulp turned around. The freighter radioed Nassau three times but got no reply. At 1:36 a.m., the Finnpulp successfully contacted the United States Coast Guard in Miami. It was the first distress call sent out.

The passenger liner Bahama Star was following Yarmouth Castle at about twelve miles distance. At 2:15 a.m., Captain Carl Brown noticed rising smoke and a red glow on the water. Realizing that this was Yarmouth Castle, he ordered the ship ahead at full speed. Bahama Star radioed the U.S. Coast Guard at 2:20 a.m.

The first ship on the scene was Finnpulp. The first of Yarmouth Castle's lifeboats, which was only half-full, rowed to the freighter. Captain Lehto was angered to find that only four of the people in the boat were passengers. The other 20 were crewmembers who fled at the first alarm, among them Captain Voutsinas. The four passengers were taken aboard the freighter. Voutsinas claimed that he had come to Finnpulp to request a radio distress call. Lehto turned Voutsinas and the crewmen back to Yarmouth Castle saying, "Go back and look for more survivors." The next two lifeboats launched from Yarmouth Castle contained only crew.

By this time, Bahama Star had arrived on the scene. The ship stopped 100 yards from Yarmouth Castle and launched her lifeboats, which lined up against the starboard side of the burning ship. Some people jumped into the water and climbed aboard the lifeboats. Others descended ropes and rope ladders. Finnpulp lowered a motorboat, which towed some of the boats to Bahama Star.

Captain Brown of Bahama Star later reported hearing sounds of great panic coming from Yarmouth Castle. He recalled hearing cabin doors being broken down, as well as glass breaking and a great many people screaming. Both Brown and Lehto spoke of a low groaning sound heard throughout the rescue, which was determined to be steam escaping Yarmouth Castle's whistle. Benches, deck chairs, mattresses and luggage were thrown from the burning ship to people struggling in the water.

Finnpulp actually pulled alongside Yarmouth Castle on the port side, and passengers stepped from the burning ship onto the deck of the freighter. Finnpulp was quickly forced to retreat to a safe distance, however, when her paint began to smoke and burn. The freighter then dispatched its lifeboats to pluck people from the water.

U.S. Coast Guard pilots in four planes flying 4,000 feet overhead later said they were nearly engulfed by the smoke and flames, which could be seen for miles.

All survivors had been pulled aboard Finnpulp and Bahama Star by 4:00 a.m., by which time Yarmouth Castle's hull was glowing red. The water around the ship was visibly boiling. Just before 6:00 a.m., Yarmouth Castle rolled over onto her port side. There was a roar of steam and bursting boilers, and she sank beneath the surface at 6:03 a.m.

Aftermath

Fourteen critically injured people were taken by helicopter from Bahama Star to Nassau hospitals. Bahama Star rescued 240 passengers and 133 crewmen. Finnpulp rescued 51 passengers and 41 crewmen. Both ships arrived in Nassau on November 13.

Eighty-seven people went down with the ship, and three of the rescued passengers later died at hospitals, bringing the final death toll to 90. Of the dead, only two were crewmembers: stewardess Phyllis Hall and Dr. Lisardo Diaz-Toorens, the ship's physician. While some bodies were recovered, most were lost with the ship.

The Yarmouth Castle fire was the worst disaster in North American waters since the Noronic burned and sank in Toronto Harbour with the loss of up to 139 lives in 1949.

Investigation

An investigation into the sinking was launched by the U.S. Coast Guard, which issued a 27-page report on the disaster in March 1966.

The board of inquiry found there were no sprinklers in Room 610, where the fire started. Mattresses had been stacked improperly close to the ceiling light, which was the ultimate cause of the fire.

Room 610 was unsuitable as a cabin because it was too hot, being located directly above the boiler room. The paneling and suspended ceiling had been removed from the room a month before the blaze, and the exposed insulation fueled the fire.

Excessive layers of paint were also found to be at fault. Walls were never stripped before being re-painted, which the board maintained was a fire hazard. Painted ropes had prevented several of Yarmouth Castle's lifeboats from being launched. Some passengers had difficulty escaping their cabins, as the clamps on the portholes had been painted over.

The Coast Guard discovered numerous other violations: No fire doors were closed during the blaze. Lifejackets were not stored in every cabin. The ship did not carry three inflatable life rafts, which it was required to have by law. There was only one radio operator on board, while the law required two. Passengers had also never been informed of evacuation procedures.

Yarmouth Castle had passed a safety check and fire drill three weeks before she burned and sank. However, the ship did not need to conform to American safety regulations since it was registered under the Panamanian flag. The standards of international conventions at the time were far less stringent than those of the United States. Also, Yarmouth Castle had been built in 1927, and did not conform to many safety rules adopted since then.

Captain Voutsinas and other members of the crew were ultimately charged with violation of duty for leaving the ship before attempting to rescue passengers.

The Yarmouth Castle disaster was followed by updates to the Safety of Life at Sea law, or SOLAS. The updated law brought new maritime safety rules, requiring fire drills, safety inspections and structural changes to new ships. Under SOLAS, any vessel carrying more than 50 overnight passengers is required to be built entirely of non-combustible materials such as steel. Yarmouth Castle's largely wooden superstructure was found to be the main cause of the fire's rapid spread.

Legacy

Canadian singer-songwriter Gordon Lightfoot wrote a song based on the tragedy. Called "Ballad of Yarmouth Castle," it was released on his fifth United Artists album, Sunday Concert, in 1969. That album, along with Lightfoot's other UA releases, was re-released in a three-CD compilation, The Original Lightfoot: The United Artists Years, in 1992. The ballad was not Lightfoot's only shipwreck-themed song; in 1976, he released his album Summertime Dream, which included the song "The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald," based on the sinking of the American-flagged Great Lakes freighter Edmund Fitzgerald in an early November gale in 1975.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Yarmouth_Castle

12 November 1965 - SS Yarmouth Castle burning

SS Yarmouth Castle was an American steamship whose loss in a disastrous fire in 1965 prompted new laws regarding safety at sea.

Yarmouth Castle sailing under her original name, Evangeline

Early history

She was built in 1927 by the William Cramp & Sons Ship and Engine Building Company in Philadelphia. She was christened Evangeline and renamed Yarmouth Castle in 1964.[1] The ship was 365 feet long and measured 5,002 gross tons. Her sister ship, Yarmouth, was launched the same year. Her sister was named Yarmouth till 1954, then renamed several times, Queen of Nassau 1954, Yarmouth Castle 1957, San Andred 1966, Elizabeth A 1967, she was scrapped in 1977.

Evangeline operated the Boston – Yarmouth, Nova Scotia service for the Eastern Steamship Lines until World War II, when she was sent to the Pacific to serve as a troop ship. The ship ferried combat troops from San Francisco to the island battlefronts and also served as a hospital ship. After being refitted and refinished at the Bethlehem Steel Corporation's shipyards at a cost of US$1.5 million, she returned to passenger service in May 1947.

She operated on the New York City – Bahamas run for less than a year, and was then laid up from 1948 to 1953, save for a two-month period in 1950. The ship was sold to a Liberian company called the Volusia Steamship Company in 1954. She was given an overnight run from Boston to Nova Scotia, and resumed service to the Caribbean in 1955.

The ship was sold in 1963 to the Chadade Steamship Company, and her name was changed to Yarmouth Castle that year. She offered service from New York City to the Bahamas for Caribbean Cruise Lines, which went bankrupt that same year. By the end of 1964, Yarmouth Castle was operated by Yarmouth Cruise Lines. The ship ran pleasure cruises on the 186-mile stretch between Miami and Nassau. She was under Panamanian registry.

Fire

Yarmouth Castle departed Miami for Nassau on November 12, 1965, with 376 passengers and 176 crewmen aboard, a total of 552 people. The ship was due to arrive in Nassau the next day. The captain on the voyage was 35-year-old Byron Voutsinas.

Shortly before 1:00 a.m. on November 13, a mattress stored too close to a lighting circuit in a storage room, Room 610, caught fire. The room was filled with mattresses and paint cans, which fed the flames.

At around 1:00, a badly burned passenger emerged from a stairway and collapsed on the deck. Crewmen who rushed to the man's aid found the stairwell filled with smoke and flames. Captain Voutsinas was immediately notified of the fire by the watch officer. The captain ordered the second mate to sound the alarm on the ship's whistle, but the bridge went up in flames before the alarm could be sounded. The ship's radio operator, who had been off duty, found the radio shack to be completely ablaze by the time he reached it. By this point, Yarmouth Castle was 120 miles east of Miami and 60 miles northwest of Nassau.

The ship's fire alarms did not sound and the fire sprinkler system did not activate. Passengers were awakened by screaming and running in the corridors as people frantically tried to find lifejackets.

Photograph of the fire taken from the boat deck of Bahama Star

The fire swept through the ship's superstructure at great speed, driven by the ship’s natural ventilation system. The flames rose vertically through the stairwells, fueled by the wood paneling, wooden decks and layers of fresh paint on the walls. Many passengers had to break windows and squeeze through portholes to exit their burning cabins. The whole front half of the ship was quickly engulfed, causing passengers and crew to flee to the stern of the ship. Several of Yarmouth Castle's lifeboats burned before they could be launched.

More problems ensued. The ship's fire hoses had inadequate water pressure to fight the fire. One of the hoses had even been cut. Additionally, the swimming pool was connected to the fire pump system by way of an open valve which allowed the pool to fill and thereby reduced water pressure. Crewmen also had difficulty launching the lifeboats. The ropes used to lower the boats had been covered in thick coats of paint, causing them to jam in the winches. Even the boats that were successfully lowered had no rowlocks, and had to be paddled like canoes. In the end, only six of the 13 lifeboats were launched.

There were tales of both courage and cowardice among the crew. Many fled the ship without helping the passengers. Others pulled passengers from the windows of their cabins and directed them to rope ladderson the side of the ship. Some crew members had to physically throw weak and panic-stricken people off the side of the ship, away from the spreading flames. Several sailors even gave away their lifejackets.

The Finnish freighter Finnpulp was just eight miles ahead of Yarmouth Castle, also headed east. At 1:30 a.m., the ship's mate noticed that Yarmouth Castle had slowed significantly on the radar screen. Looking astern, he saw the glowing flames and notified the captain, John Lehto, who had been asleep. Lehto immediately ordered Finnpulp turned around. The freighter radioed Nassau three times but got no reply. At 1:36 a.m., the Finnpulp successfully contacted the United States Coast Guard in Miami. It was the first distress call sent out.

The passenger liner Bahama Star was following Yarmouth Castle at about twelve miles distance. At 2:15 a.m., Captain Carl Brown noticed rising smoke and a red glow on the water. Realizing that this was Yarmouth Castle, he ordered the ship ahead at full speed. Bahama Star radioed the U.S. Coast Guard at 2:20 a.m.

The first ship on the scene was Finnpulp. The first of Yarmouth Castle's lifeboats, which was only half-full, rowed to the freighter. Captain Lehto was angered to find that only four of the people in the boat were passengers. The other 20 were crewmembers who fled at the first alarm, among them Captain Voutsinas. The four passengers were taken aboard the freighter. Voutsinas claimed that he had come to Finnpulp to request a radio distress call. Lehto turned Voutsinas and the crewmen back to Yarmouth Castle saying, "Go back and look for more survivors." The next two lifeboats launched from Yarmouth Castle contained only crew.

By this time, Bahama Star had arrived on the scene. The ship stopped 100 yards from Yarmouth Castle and launched her lifeboats, which lined up against the starboard side of the burning ship. Some people jumped into the water and climbed aboard the lifeboats. Others descended ropes and rope ladders. Finnpulp lowered a motorboat, which towed some of the boats to Bahama Star.

Captain Brown of Bahama Star later reported hearing sounds of great panic coming from Yarmouth Castle. He recalled hearing cabin doors being broken down, as well as glass breaking and a great many people screaming. Both Brown and Lehto spoke of a low groaning sound heard throughout the rescue, which was determined to be steam escaping Yarmouth Castle's whistle. Benches, deck chairs, mattresses and luggage were thrown from the burning ship to people struggling in the water.

Finnpulp actually pulled alongside Yarmouth Castle on the port side, and passengers stepped from the burning ship onto the deck of the freighter. Finnpulp was quickly forced to retreat to a safe distance, however, when her paint began to smoke and burn. The freighter then dispatched its lifeboats to pluck people from the water.

U.S. Coast Guard pilots in four planes flying 4,000 feet overhead later said they were nearly engulfed by the smoke and flames, which could be seen for miles.

All survivors had been pulled aboard Finnpulp and Bahama Star by 4:00 a.m., by which time Yarmouth Castle's hull was glowing red. The water around the ship was visibly boiling. Just before 6:00 a.m., Yarmouth Castle rolled over onto her port side. There was a roar of steam and bursting boilers, and she sank beneath the surface at 6:03 a.m.

Aftermath

Fourteen critically injured people were taken by helicopter from Bahama Star to Nassau hospitals. Bahama Star rescued 240 passengers and 133 crewmen. Finnpulp rescued 51 passengers and 41 crewmen. Both ships arrived in Nassau on November 13.

Eighty-seven people went down with the ship, and three of the rescued passengers later died at hospitals, bringing the final death toll to 90. Of the dead, only two were crewmembers: stewardess Phyllis Hall and Dr. Lisardo Diaz-Toorens, the ship's physician. While some bodies were recovered, most were lost with the ship.

The Yarmouth Castle fire was the worst disaster in North American waters since the Noronic burned and sank in Toronto Harbour with the loss of up to 139 lives in 1949.

Investigation

An investigation into the sinking was launched by the U.S. Coast Guard, which issued a 27-page report on the disaster in March 1966.

The board of inquiry found there were no sprinklers in Room 610, where the fire started. Mattresses had been stacked improperly close to the ceiling light, which was the ultimate cause of the fire.

Room 610 was unsuitable as a cabin because it was too hot, being located directly above the boiler room. The paneling and suspended ceiling had been removed from the room a month before the blaze, and the exposed insulation fueled the fire.

Excessive layers of paint were also found to be at fault. Walls were never stripped before being re-painted, which the board maintained was a fire hazard. Painted ropes had prevented several of Yarmouth Castle's lifeboats from being launched. Some passengers had difficulty escaping their cabins, as the clamps on the portholes had been painted over.

The Coast Guard discovered numerous other violations: No fire doors were closed during the blaze. Lifejackets were not stored in every cabin. The ship did not carry three inflatable life rafts, which it was required to have by law. There was only one radio operator on board, while the law required two. Passengers had also never been informed of evacuation procedures.

Yarmouth Castle had passed a safety check and fire drill three weeks before she burned and sank. However, the ship did not need to conform to American safety regulations since it was registered under the Panamanian flag. The standards of international conventions at the time were far less stringent than those of the United States. Also, Yarmouth Castle had been built in 1927, and did not conform to many safety rules adopted since then.

Captain Voutsinas and other members of the crew were ultimately charged with violation of duty for leaving the ship before attempting to rescue passengers.

The Yarmouth Castle disaster was followed by updates to the Safety of Life at Sea law, or SOLAS. The updated law brought new maritime safety rules, requiring fire drills, safety inspections and structural changes to new ships. Under SOLAS, any vessel carrying more than 50 overnight passengers is required to be built entirely of non-combustible materials such as steel. Yarmouth Castle's largely wooden superstructure was found to be the main cause of the fire's rapid spread.

Legacy

Canadian singer-songwriter Gordon Lightfoot wrote a song based on the tragedy. Called "Ballad of Yarmouth Castle," it was released on his fifth United Artists album, Sunday Concert, in 1969. That album, along with Lightfoot's other UA releases, was re-released in a three-CD compilation, The Original Lightfoot: The United Artists Years, in 1992. The ballad was not Lightfoot's only shipwreck-themed song; in 1976, he released his album Summertime Dream, which included the song "The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald," based on the sinking of the American-flagged Great Lakes freighter Edmund Fitzgerald in an early November gale in 1975.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Yarmouth_Castle